The most concrete municipal commitments which arose from the summer of 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests in Seattle came in the form of multi-million dollar investment pledges, the first of which has already been allocated. But there are serious questions about what, precisely, Seattleites are getting in return for this spending.

The goal of this first tranche was to commission a research team with $3 million to do qualitative research to better inform the participatory budgeting process to follow. But recently, in an open letter to the community, the entity that was commissioned (which originally consisted of King County Equity Now and a research team within it) announced they are splitting up. This, just a couple weeks before their final report is due.

This sudden split apparently came as a surprise to the overseeing councilmember Tammy Morales, according to her quote to SCC Insight:

My office was made aware of a letter circulating from the Black Brilliance project. I haven’t yet been briefed by my staff but I intend to get up-to-speed immediately and make contact with the stakeholders as we ensure that this vital research work is seen to completion to inform the upcoming participatory budgeting process. While I learn more about the detailed grievances, the work itself remains critically important to inform policies that impact Black and Brown communities.

Councilmember Tammy Morales to SCC Insight, February 8 2021

That she was apparently caught off-guard by this raises further questions about the meaning of municipal oversight, as well as the wisdom of the hasty kickoff process here, which never was bid-out, and began without even narrowing down key metrics for evaluation.

I would encourage you to read SCC Insight’s list of questions posed to Councilmember Morales about the funding process and her response, here.

Background

During the summer of 2020, Mayor Durkan created the Equitable Communities Task Force, which will be distributing $100 million in annual funding to communities of color and program initiatives, after running their own resource allocation process.

$100 million is not a small sum. It’s 6.7% of the city’s fiscal year general funds budget, beyond existing city services.

The Seattle City Council allocated $3 million of this to the Black Brilliance Project and King County Equity Now late in the summer, to research community-led solutions public safety and health. The purpose of this research is to better inform $30.275 million of participatory budgeting investments which would follow. That $30.275 million is subject to future Council ordinances.

Specifically, the $3 million is to “research processes that will promote public safety informed by community needs.”

I have no problem with investments; we need them to strengthen communities, advance more opportunity and achieve better outcomes. But as I wrote on this blog back in July, our city’s history of allocating funds to third parties has been broken for quite some time:

Seattle has a terrible record of doling out funds to third party service providers; so little accountability, so little check-ins, audits, definitions of success metrics, and ongoing measurement. The result has largely been paydays for third-party service providers, who, once entrenched, are rather difficult to see into.

Seattle Plows Ahead with 50% Cut To Police Department. Where are the Metrics Which Define Success? – July 11, 2020

Which brings me to today’s post, a brief check-in on one of these components: the Black Brilliance / King County Equity Now research effort (i.e., the $3 million allocated.)

Let’s Improve Public Safety and Health

Let me first state that like you, I’m all for better approaches to public safety and health, particularly in minority communities, and also throughout the city. There are clear disparities in public safety outcomes by different communities in the city, and we should always strive to understand their drivers and close the gaps and invest in ways that deliver better outcomes.

But to me, the most sensible way to begin such a process of improvement is to first define which metrics most indicate the goal of improved public safety and public health, prioritize them, and work backward from there.

Everyone can and should say we want better public safety and public heath.

Specifically though, are we wanting to lower assaults by 10-30% in three years? Reduce property crime reports by 20%? Reduce reports of unwarranted and/or illegal police violence? Lessen addiction? Recidivism? Reduce calls to 911? Improve lifespan? For which age groups? By how much? What’s been the existing trend? Who will own the reporting, and how often will this measurement be done?

“Yes” to all questions isn’t actionable.

We can and should answer “yes, we’d like to improve!” to all of the above, but resource allocation is about tradeoffs. And “yes” to all questions isn’t actionable. The strategy for reducing assaults will likely look different than the strategy for reducing diabetes or COVID risks. The strategy for reducing youth violence will likely look different than the strategy for improving transit and work options.

Investing dollars and attention into Initiative A means that you necessarily will have less to invest in Initiative B. And unless you’re omniscient, you need to measure what the current baseline is, or else you might be swayed by anecdotal reports, when actual trends are moving in the opposite direction.

In other words, it’s important to first determine what matters (yes, it’s subjective, but choosing and ranking is part of leadership!), then measure the current lay of the land, and get past measures, to calibrate the trajectory.

OK, so which public safety and health metrics are most important right now? Which are most leveraged, where the return on investment goes highest, or where return can be most rapid?

Which metrics are we most alarmed by, and how can we measurably improve them? Who owns the measurement of those metrics? How are they trending? What improves them or worsens them?

Getting to the bottom of these prioritized metrics seems a worthy goal of research. So does softer qualitative research, which better informs things like attitudinal views, historic influence, and more — all of which might for instance encourage better take-up of new initiatives and ultimately better results.

But research must have a guiding north star to be actionable. “We need to invest in everything” is not any more helpful than what we know now. Without spending $3 million, I can make that statement. Prioritization and resource allocation is a key role that municipal leaders should play — setting the goals that we wish to improve.

But that’s not what Seattle leadership has done here. Let’s take a look at their knee-jerk approval process, and where we are today.

The process is now under state audit, and I’m guessing the full auditors report of this process is going to be pretty revealing. Let the distancing begin.

Mistake #1: Absence of Success Metrics.

When this process began, lots of city council members said we need to improve public safety and health outcomes in Seattle, particularly in BIPOC communities, but no one offered any metrics that identified what those might be. During the entire summer, I listened to Council Zoom after Council Zoom, waiting for anyone to state how we measure these laudable goals as we “reimagine policing to invest in communities for better outcomes.”

The only one to venture close to that was Dan Strauss, who said that he’d be looking at response times, and whether the right parties arrived on scene at the right time with the right resources. OK, that’s a starting point — but who measures? How often? Etc. The statement stopped there. Just as bad, the starting benchmark seems to be ignored. As Tim Burgess and others have pointed out, our police response time goals are not even meeting the bar today, nor are they moving in the right direction.

Further, though it might surprise some, there is considerable data both in Seattle and nationally that the vast majority of Black Americans do want to retain local police presence. They, and we, just want it to be better — more transparent, more accountable, more subject to scrutiny, less prone to use of force when not necessary, and more.

To me, all this suggests continued reform, rather than abolition. But what metrics, specifically, constitutes “better?” That’s where research can come in, and should. I’d say things like response times, reduction in assaults, shootings, property crime and more would be eligible for metrics to consider, as are many others. But the discussion never seems to venture into the metrics, and certainly never seems to get to the prioritized five or ten which best indicated success or failure in leaders’ views.

Mistake #2: This research appears fully disconnected from a parallel initiative, didn’t earn the Executive Branch’s support, and was already fractured.

Check out this article from The Urbanist: 19 Black Leaders Decline Invite to Durkan’s Equitable Communities Task Force | The Urbanist. It’s pretty clear these two efforts weren’t united from the start.

The Seattle City Council is the legislative branch of the city. The Mayor runs the Executive Branch of the city. Each has their own initiatives. It makes little sense to me why the Council-driven $3 million research plus follow-on $30.275 million investment is wholly separate from the Mayor’s $100 million initiative, especially when the council’s specific goals with this research are so unclear and un-prioritized. Shouldn’t there be some alignment there?

Mistake #3: It was a No-Bid Contract.

As SCC Insight pointed out in December in a must-read, much-more-informed backgrounder to this whole affair, the city’s municipal code requires that consultant services such as this be put out to bid.

This was not done.

Why not? Well, you’ll have to make your own guesses here. Publications like SCC Insight need to be a bit more generous in their assumptions than I need to be in my own personal blog. I’d say that given the evidence, reasonable guesses include the possibility that City Council had specific designated suppliers or community members it wished to engage in this work and receive the funds, or perhaps it had a timeline that was particularly urgent, or both, or some other rationale.

Regardless, the contract was not put up for bid. The city did not advertise this consultant contract as required by the Seattle Municipal Code.

Now, the municipal code does allow no-bid contracts to take place, but they must go to a “public benefit organization,” i.e., a 501(c)3 organization. But here again, there was a hurdle — King County Equity Now (KCEN) was not at the time a 501(c)3, though they are in process of forming one now.

So what did the City Council do? They enlisted Freedom Project, an existing Seattle-based 501(c)3 to be a “fiscal agent” — i.e., a money managing intermediary — to dole out the funds on a contract that was never put out to bid. And in fact, Freedom Project is also a participant in the survey research going on.

Mistake #4: Research Contract Was Awarded to an Entity With a Clear, Pre-existing Policy Agenda.

Either the City Council should invest money to advance a policy agenda that it believes is correct, or pay an independent third party with a clear track-record of independent research to gather input and evaluate alternatives. But not both.

Here, the City Council decided to award a lofty sum of $3 million to an organization — King County Equity Now — that has a very specific policy agenda (police defunding and reinvestment in communities.)

In fact, the principal researcher herself, Shaun Glaze, was by her own account in the BBR’s open letter a key architect of the “divest in police” blueprint: “Shaun was a principal drafter of the Blueprint for Divestment/Investment presented to the Seattle City Council this summer by KCEN and Decriminalize Seattle, and Shaun facilitated the development of the budget and blueprint for the $3 million Black Brilliance Research Project.”

Yet she’s also leading the research. That’s hardly independence from an agenda.

Perhaps hers is the right policy agenda. Perhaps it’s not. But why is the council paying $3 million — a pretty massive sum for research — to an organization when, in many ways, it appears that same group has already made up its mind what that research should conclude? Has the methodology been subject to any kind of independent review? Starting to sound a bit off? You be the judge.

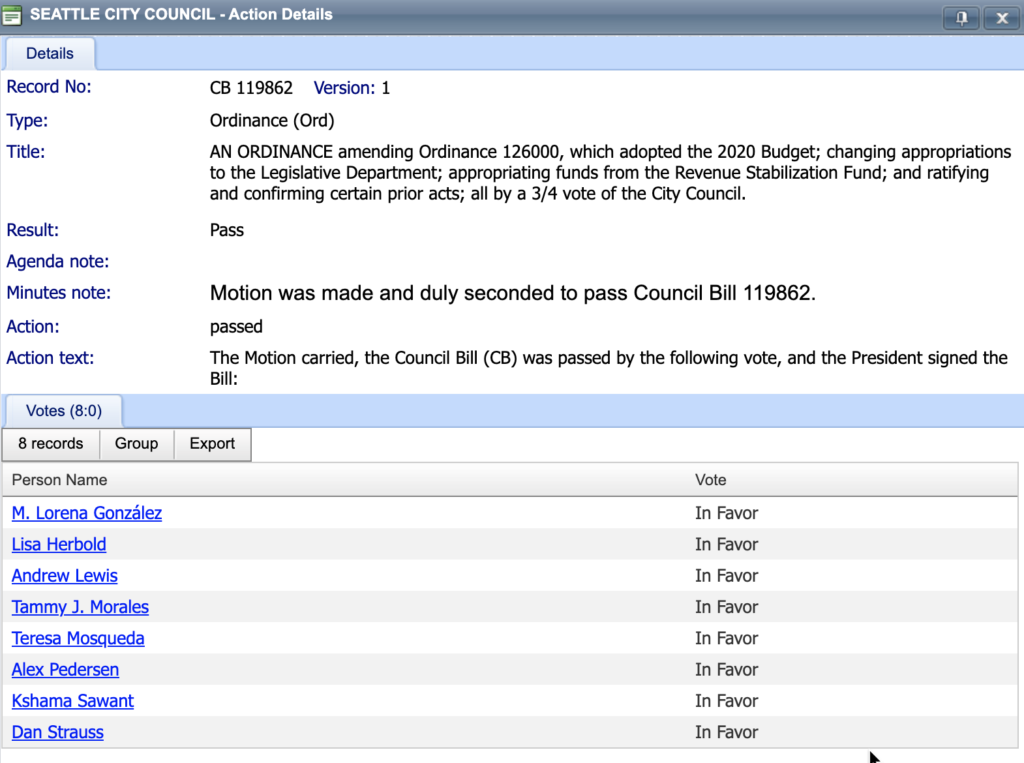

Mayor Durkan was not in favor of this spending, at least not the way this spending was proposed, and so she vetoed the legislation. But the City Council overrode her veto, appropriating $3 million from the city’s Revenue Stabilization Fund to this research project. The vote was 8-0, with Councilmember Debra Juarez not present for that vote.

Open Question: Research Methodology

Beyond taking a few graduate-level statistics, applied math and marketing research classes, my research credentials honestly just aren’t strong enough to validate or critique the research methodology. The primary researcher, Shaun Glaze, holds a PhD from Boston College in Applied Developmental and Educational Psychology, including plenty of research and analysis positions and projects.

I do wonder about how objective a process can be if it starts out being under the auspices of an organization which has a specific policy agenda, or at a minimum what safeguards City Council established to ensure that the advocated policy slate was not a fait accompli. The split, from that standpoint then, makes some sense for Seattleites if it signals that the output can be more independent in nature, without any pre-existing policy agenda it seeks to validate.

But the preliminary report was completed under the auspices of King County Equity Now, and KCEN has a clear policy agenda. Were any inputs or outputs be filtered through that lens? Were questions leading?

Put more directly, is the purpose of this research to validate a pre-existing set of recommendations, or is it truly open to whatever conclusions arise, even if, say, reduction in police isn’t something that’s favored?

A large part of the surveying effort surrounds the question “If you had $200 million to reinvest into creating more community safety and health, how would you reinvest it?” Note that they are not asking participants to weigh whether the local police force should be de-funded to achieve that $200 million, just starting with the assumption that it’s found money. Participants might plausibly answer differently if asked “The Seattle Police Department has 15 police officers per 10,000 citizens, where other cities like Boston have about 40. Should we further de-fund the police?” Or “Are police response times adequate for your neighborhood?” Or “Should we increase community policing in your neighborhood?”

Beyond that, it’s worth having research experts look at matters of statistical significance and sampling methods used. For instance, how representative is the sample of respondents to the overall BIPOC population in Seattle? In the preliminary report, the researchers indicate that they “heard from over 4,000 community members” but had, at the time of the preliminary report 1,382 respondents to a detailed survey. Were these sampled randomly? It doesn’t appear so.

To calibrate this, according to the Census, the makeup of Seattle’s 750,000 citizens is: 65.7% white, 14.1% Asian, 7% Black, 6.6% Hispanic or Latino, 0.4% Native American, 0.9% Pacific Islander and other. That means Seattle’s population is approximately 8%-16% BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color), depending upon whether you include Asian, Latino and Pacific Islander in the BIPOC designation.

The 2016 Census suggests there are on the order of 50,000-60,000 Black individuals calling Seattle home, and perhaps north of 100,000 Seattleites who would fit in an expanded definition of BIPOC. One question — is 1,382 completing the survey, skewing significantly younger than the overall Seattle population — representative? On page 18 of the preliminary report, they state that 60% of the respondents are under the age of 45, but didn’t clarify how closely matched the various cohorts are to Seattle’s age distribution: According to the 2016 census, 5.6% of Seattleites were under the age of 18, 11.9% from 18 to 24, 38.6% from 25 to 44, 21.9% from 45 to 64, and 12.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.8 males.

I ask these questions not knowing the answer. I don’t know. And there is use in qualitative feedback and focus-group level work, for sure.

But these and other methodology questions and outputs are useful to know, as they are with any rigorous qualitative study.

SCC Insight posed some questions related to the methodology to Councilmember Morales. Here is her response, taken in full from SCC Insight’s piece Catching up with the Mayor’s task force and the Black Brilliance research project (sccinsight.com):

Thanks for your patience as I try to catch up from the budget process. To respond to your questions about the participatory research contract and process, I’ll start by saying that I reject the premise of some of your questions that the researchers aren’t ‘qualified’ or don’t ‘know what they are doing.’

More to the point, the contracts which have predated this one haven’t received the same kind of scrutiny you’re offering here. So, I find it interesting that this particular contract has received so much attention from the onset.

What I will say about this work is that the notion that a ‘bottom up’ approach is subpar misses the point of participatory research. The issue is not whether this is a typical research project but is instead entirely about how to teach community members exactly how to critically analyze the impact of policy on their neighborhood. (It’s access to power that my community has never enjoyed.) We could have contracted with a university and had graduate students doing this research, but that would not have produced the outcomes we’re looking for. Participatory research is about building the capacity of our neighbors to understand what’s happening in their community and to increase civic engagement so they can inform future policy-making. This is what we mean when we say “DEMOCRATIZING power and resources.”

To suggest that a greater standard or threshold is in order is to dismiss the people who stand to benefit most from this approach, which – while newish to Seattle – IS a standard in NYC, Chicago and Barcelona too.

The research methodology for this contract was developed by professional researchers, PhDs in research who are professionally credentialed, and who are also coordinating the research and the community researchers.

Regarding the contract itself, there are several approaches to contracting; and, it is standard operating procedure to use contracting through fiscal agents for organizations that have not established 501C3 status. The $3 million was based on the work and anticipated expenses included in the Blueprint proposal. And yes, I am very confident that this participatory research process and the investment in building community capacity will prove valuable to the City.

I hope that answers your questions.

Tammy

Kevin Schofield, editor/owner of SCC Insight added:

If Council member Morales thinks that this level of scrutiny is new or unique, then she hasn’t read SCC Insight’s prior articles on the soda tax, TNC drivers’ pay, court fines and traffic stops, the Point in Time count, SPD internal research, and e-scooters. And to reiterate: at $3 million, this is much larger than the vast majority of the city’s research contracts, and as such is deserving of scrutiny.

You can see the exchange here.

Deadlines are Approaching… and an Audit.

On February 1st, 2021, an update was delivered to city council on this $3 million project.

Here’s the presentation:

Presentation-2121And here’s the preliminary report, all 1,045 pages of it:

Participatory Budgeting Preliminary Report (1045 pages) – DocumentCloud

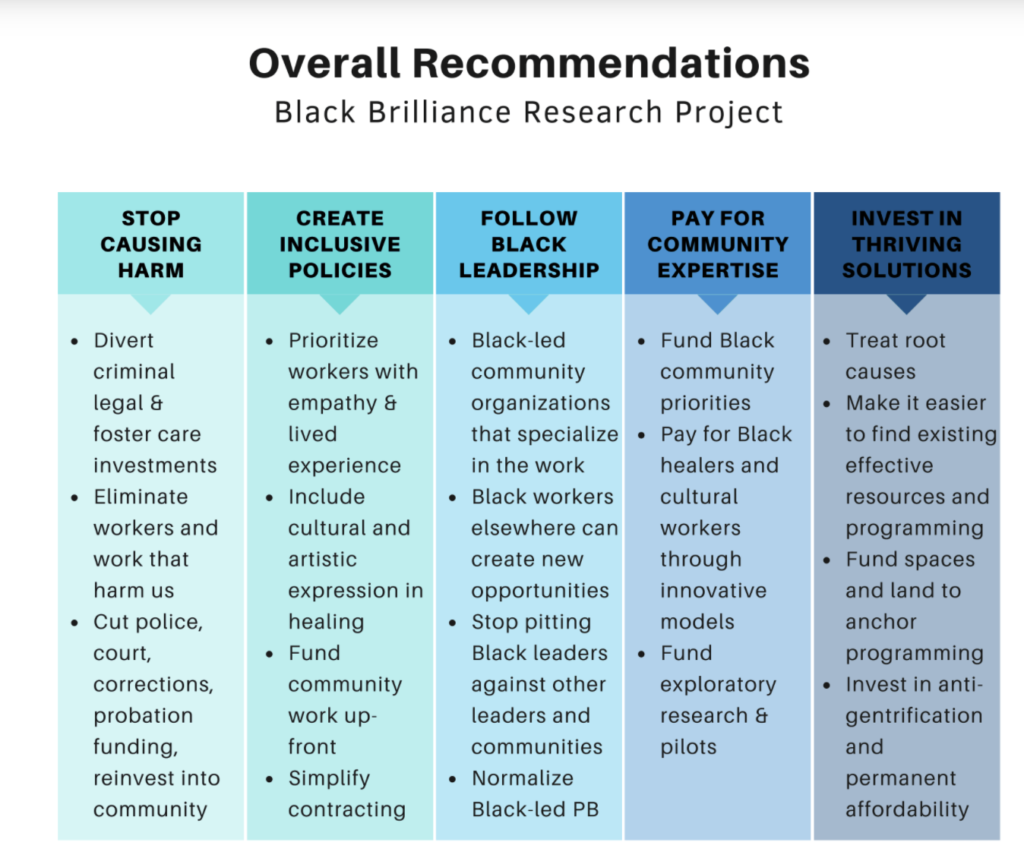

Among the key pages is this chart:

Without metrics which define better public safety and health outcomes, no one can test the validity of the recommended strategies above, nor compare them to what has been tried and works elsewhere. For instance, the key recommendations in the leftmost column seem to directly conflict with Gallup’s polling here, as well as privately-funded analysis of ten years of calls for service by SPD.

Do we let evidence guide us? We should. Doing that requires measuring, developing comparables, and making adjustments.

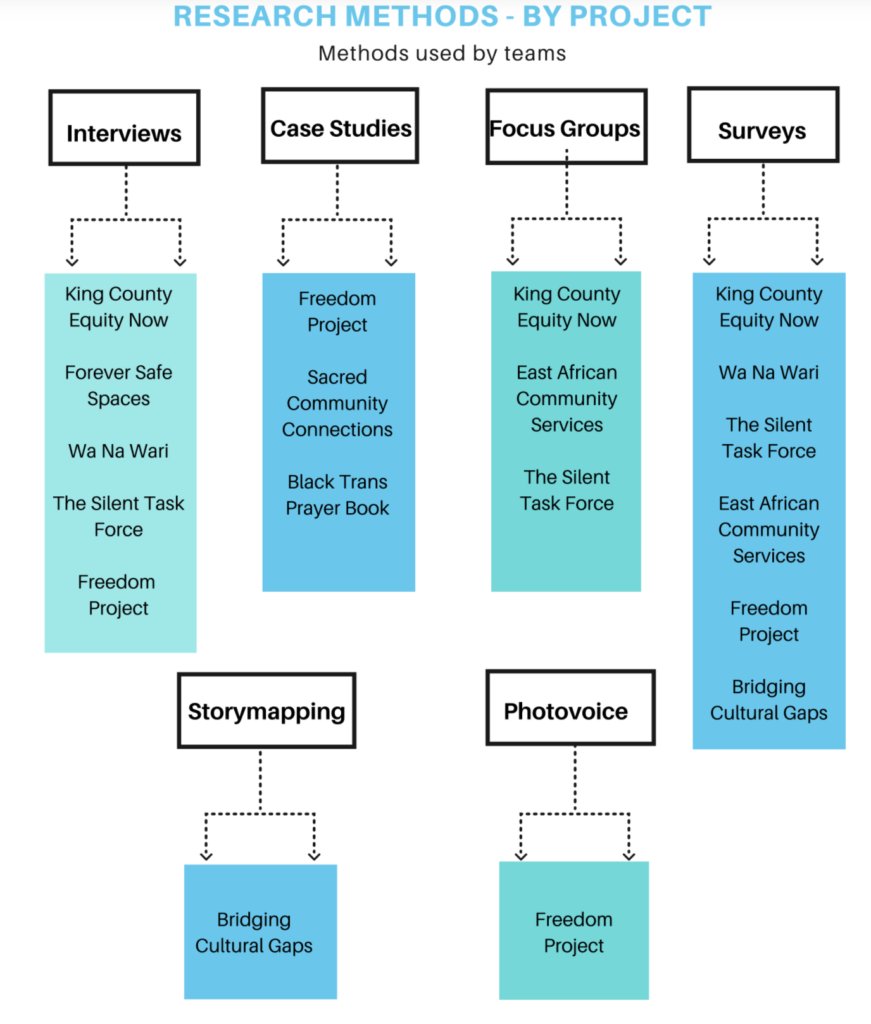

On page 24, they outline the research methods by project:

Note that Freedom Project, the fiscal agent, is involved with several of these methodologies. It’s probably too early to judge the output based on the preliminary report, but remember, this is the preliminary output from $3,000,000 in your tax dollars. $3 million is enough to pay a team of 30 people $100 per hour for 25 weeks.

A final report is due February 26th, so we’ll be better able to make an assessment then of just what the tangible return on investment has been.

Meanwhile, the state auditor’s office is examining the contract. Per Crosscut‘s coverage of the audit, a spokesperson for King County Equity Now said, “the state has now chosen to place an unprecedented amount of scrutiny on a small research project contract to Black community organizations. Worse, though unsurprisingly, this small contract includes some of the only public funding designated specifically for Black community aid in 2020.”

Expect some distancing statements by city officials as that report arrives.

KCEN and Black Brilliance Split

Meanwhile, prompting this writeup, in an Open Letter, researcher Shaun Glaze announced a big split between the two central parties this $3 million was allocated to.

Turmoil Surfaces in Seattle City Council’s Push to Reimagine Public Safety, Seattle Times, February 9th

Black Brilliance Research Project effort fractures (sccinsight.com)

We Must Change How We Allocate Resources

In my view, this whole episode sheds light into the shoddy process of resource allocation of city (i.e., taxpayer) dollars. Don’t we owe those who need these funds so desperately better oversight?

- The City Council spun up a parallel effort to the Mayor’s $100 million community initiative

- The City Council deliberately went around the existing municipal code to put research contracts out to bid.

- The City Council, as clients, haven’t specified clearly what prioritized (or even top 10) metrics best define “better public safety” or “better public health”, and seems rudderless in the effort. It makes the resulting “research” an exercise in putting some data together, without any clear metric by which to measure “were we correct?” Will we know whether those $3 million are well-spent? Which numbers will move?

The state auditor will have much more to say about this soon, and I’ll link to the report when available.

A Better Process

Clearly, we can already see that there are major problems here, can’t we? Is this the best way to spend $3 million dollars from the City of Seattle’s Revenue Stabilization Fund?

Look. I’m just a guy with a blog who cares about our city. But even I can see that there are clear problems with the process.

Here are just a few ways this process should have been improved:

- Align the $100 million Equitable Communities initiative with this initiative. Get all the wood behind the arrow, and make it measurable.

- Leaders should first define what metrics constitute better safety and health outcomes. These should be measurable, and benchmarked. It is likely that some metrics are particularly poor and deserve extra focus, while other metrics are relatively good and deserve comparatively less attention.

- Municipal code should have been followed. It’s there for a reason, and a lot of those reasons have already shown up. A research contract should have been put out to bid. It was not. The organization should have been an official public benefit organization — the 501(c) 3 process imposes some structural elements that might have helped avoid this situation. Perhaps doing those two things — i.e., following the municipal code — would have put up some sensible guardrails here.

- The lead council member should not be surprised by news that the two key entities involved in this research are splitting. She appears to be, at least according to her statement at the end of this piece. What was the monitoring or check-in process? Is there any? It needs to be tightened. City Council has a fiduciary duty to the taxpayers of this city that the funds be well-spent. When the lead councilmember is as surprised as the rest of us about this split despite rumors which preceded it, I have no confidence that they are.

What is Participatory Budgeting?

The key goal of this research is to better inform the participatory budgeting process. What is participatory budgeting?

A good overview video is below, from King County Equity Now.

My opinion? I think participatory budgeting (in business this is often called “bottoms-up budgeting,” letting the key stakeholders define the needs) makes a lot of sense.

But I don’t think the several very good examples provided in the video should cost $3 million in advance of it.

And as clearly indicated in the video, such processes are pretty open-to-all, transparent, and collaborative. They also appears to be run by volunteers. So why $3 million? I’m guessing that these compelling examples from other cities about concrete found-wins (e.g., bus arrival signs and more) did not begin with $3 million blanket grants with very unclear deliverables and lack of oversight, but I’d be happy to be corrected if someone drops me a note that these cities all spent $3 million or so in preliminary research leading up to it.

Related Reading

Black Brilliance Research Open Letter to Community | by Shaun Glaze | Feb, 2021 | Medium

19 Black Leaders Decline Invite to Durkan’s Equitable Communities Task Force | The Urbanist

Black Brilliance Project | South Seattle Emerald

Seattle’s $3M contract to research public safety under state scrutiny | Crosscut

Black Brilliance Research Project effort fractures (sccinsight.com)

Catching up with the Mayor’s task force and the Black Brilliance research project (sccinsight.com)

Website: King County Equity Now

Postscript: Please Consider Supporting SCC Insight

Finally, a plug for a resource that I think is vital toward better city governance.

Beyond being a reader, I have no affiliation with SCC Insight, nor any of the entities mentioned above, other than being a fellow resident of this city which we all love.

But I strongly encourage Seattle-area readers join me in supporting SCC Insight on Patreon. At a minimum, follow them on Twitter. Kevin Schofield and his team of independent journalists do very good, detailed long-form research and reporting on municipal issues that is rarely offered elsewhere, at least without a driving agenda which distorts the output. SCC Insight is as close as you’ll find to “let the facts lead where they may” reporting on municipal governance in Seattle. It forms the background on much of my OpEd above. Continued thanks to them for their work.

Updates/Corrections

February 11 2021: According to this piece in Crosscut, the $30 million + $3 million is not separate and apart from the $100 million Equitable Communities initiative; Council divided up the $100 million pledge. Text has been corrected above.

…how that money gets out the door has been the subject of disagreement. Durkan pledged $100 million for projects identified by a task force of her creation. But trust in Durkan runs low in much of the activist movement and among some members of the city council. As a result, the council took her $100 million pledge — plus other investments of their own — and broke it up into different pots.

The council left $30 million for Durkan’s task force while spreading out the rest elsewhere, including $30 million to be doled out via a “participatory budgeting” process — budgeting with heavy community input — that would be organized and led by King County Equity Now.

Seattle’s $3M contract to research public safety under state scrutiny | Crosscut