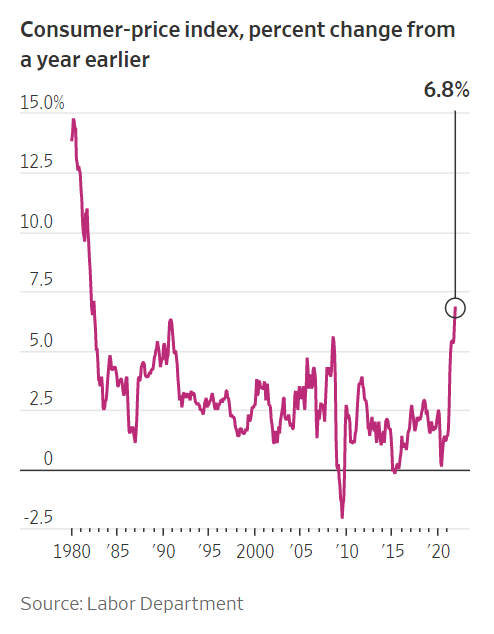

The Department of Labor announced this morning that the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) increased 6.8% before seasonal adjustment for the 12-month period ending in November 2021. That’s a little more than twice the annual average of the past 15 years. This condition is new for about a hundred million working Americans. Consider that the last time America’s annual inflation was this high, you hadn’t ever heard the term “e-mail.” Millions of American households are under pressure, and therefore so are Democrats just as 2022 midterm campaigning is set to begin.

The CPI-U is an index that attempts to estimate the cost of a basket of goods and services approximating the spending of metropolitan-area consumers, who collectively represent about 92% of all Americans.

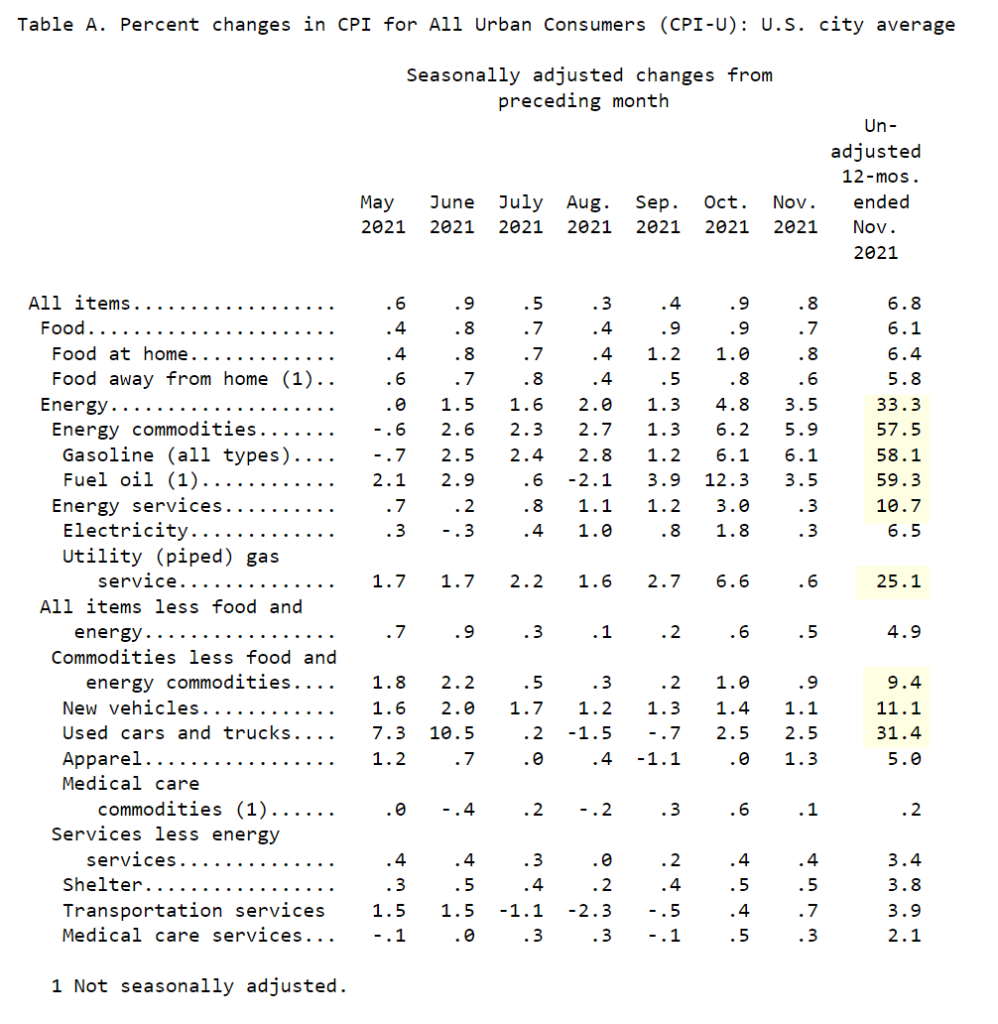

On an unadjusted basis, the line items which soared most dramatically over the period were petroleum-based energy (both gasoline and natural gas), vehicles, particularly used cars and trucks, and food, especially meat.

Making spring, summer and fall headlines, gasoline prices have shot up 58.1% over the last twelve months, the largest increase since 1980.

On the positive front, increases in rent and shelter were relatively modest, and medical care commodities and services thankfully rose very slowly.

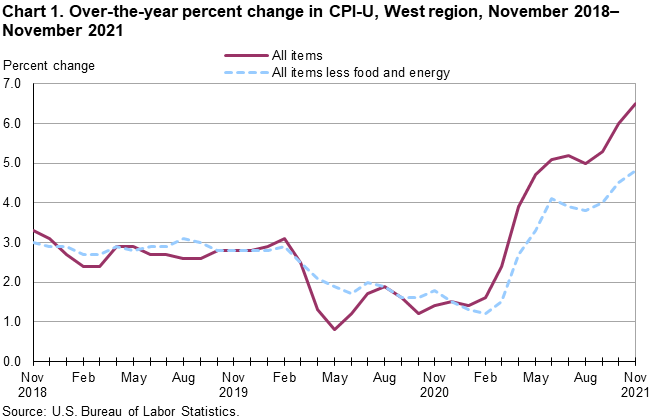

Washington State and the West

The Department of Labor provides a Western regional breakout, which includes Alaska, Arizona, California, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon and Washington. Our region’s inflation was just under the national average; prices are up 6.5% from one year ago. Gasoline prices were the West’s single biggest contributor to escalating prices, and all items minus food rose 4.8% over the year. Three of the biggest reasons for inflation in the Western US were meat (+15.4%), natural gas (+21.6%) and transportation (+19.7%.)

At the heart of several of these line-items are carbon energy prices. Taken as a whole, Energy prices rose 30.0% over the past 12 months, its largest 12-month increase since September 2005. Gasoline prices rose 49.6% in the West, and now sit at their highest level since September 2014.

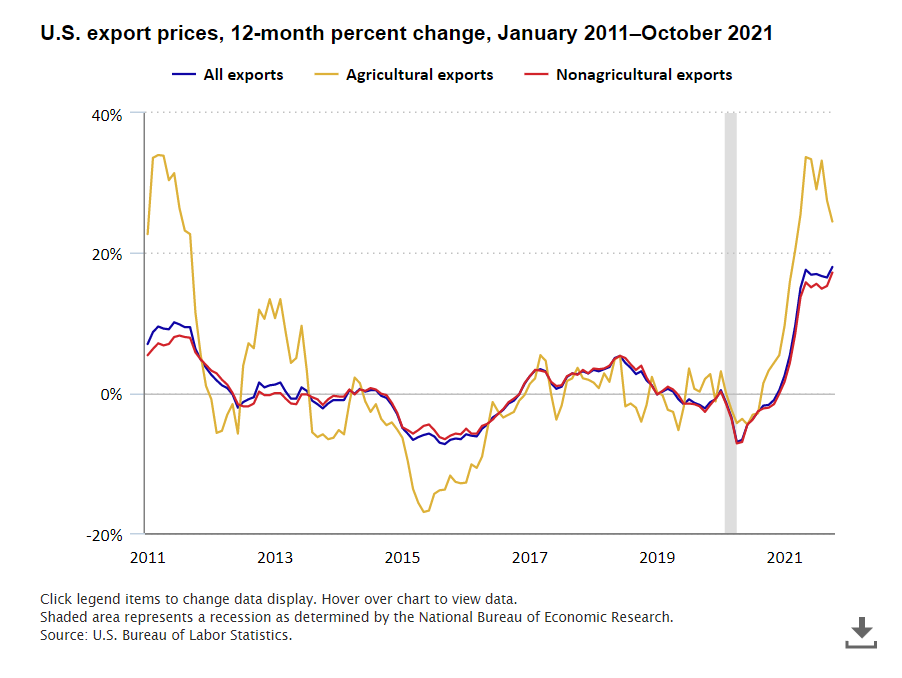

American goods aren’t just more expensive for Americans, but for the rest of the world, too. In late November, the Bureau of Labor and Statistics reported that prices for U.S. exports rose 18% for the twelve months ending October 2021. That’s the largest increase since they began publishing the index (1984.) Such price hikes to the rest of the world may reduce consumption from American goods in the future, as these record-high spikes will surely offer a stronger incentive to consuming nations to produce and buy their own goods where they can.

This is new territory for a lot of Americans. True, we’re not yet in era of double-digit increases per the late 1970’s, but roughly 7% is closer to double-digit inflation than it is the recent-past 2%-3% range. You have to go back nearly four decades to see these rates, which means that most working Americans haven’t ever seen such high increases in prices before, and that brings with it huge political ramifications.

Even if you received a 5% pay raise this year, your daily budget lost ground (5% – 6.8% = -1.8% change in real earning power), assuming the basket of goods and services you buy are roughly equal to that which underpins the Consumer Price Index.

Inflation can be thought of as a particularly pernicious form of regressive taxation, hitting low-income households hardest of all. High-income consumers who could waltz through a Whole Foods, unbothered about prices in 2019 won’t feel much impact from nearly 7% inflation. But if you’re watching every penny, this hits very, very hard.

Inflation is therefore very often political poison to the party in charge. NPR has the receipts. After Republicans lost the White House and got wiped out in Congress during the mid ’70’s Watergate era, they were reduced to barely one-third of the seats in both houses of Congress. Despite this, President Carter, saddled with a combination of bad luck of new-found OPEC cartel muscle and some poor messaging and decision-making exacerbating inflation, saw inflation rise from 6.5% in 1977 to 18% during his re-election run of 1980. With prices soaring, the Fed sharply hiked interest rates at the worst time for him, bringing on a major recession just in time for the re-election. And Reagan won in a landslide.

Today, OPEC is less powerful, and not the primary cause of our woes. What’s behind these sharp increases? They’re more likely the result of a perfect storm:

- Massive injections of federal spending in two waves (first during the Trump administration and again at the start of the Biden administration)

- Monetary easing by the Federal Reserve, lowering interest rates making borrowing cheaper

- Executive office decision-making regarding energy, such as halting gas pipelines, and placing limits on exploration, which reduced the pace of American energy production

- Supply-chain woes, exacerbated by a variety of factors (high demand, clogged ports, lack of truck chassis, new regulations and limits placed on offloading)

- Increased pricing power by large corporations, as small businesses struggle relatively more during the pandemic

- Increased consumer demand

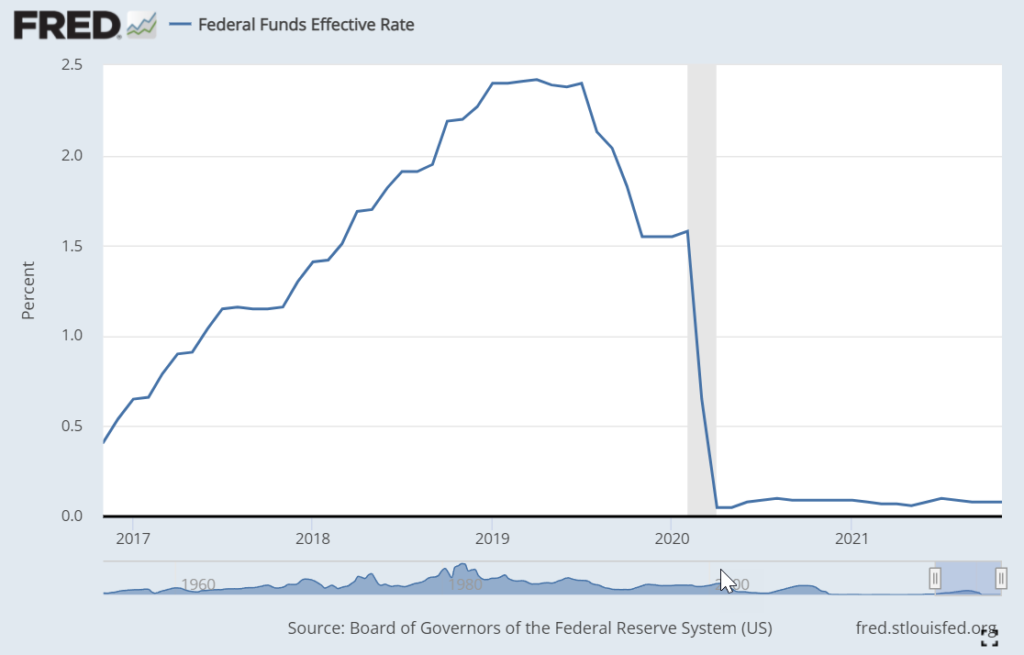

The Fed has two primary governing legislated mandates: they are to promote price stability and full employment. When the pandemic hit, correctly predicting major disruption to economic activity, the Federal Reserve opened the floodgates.

How? The Fed’s primary way to do so is to adjust interest rates. The Fed sets both the rate at which banks can borrow amongst themselves (the “fed funds rate”) and also the rate at which banks can borrow directly from the central bank of the United States (the “discount rate.) By setting these two interest rates, the Fed can make money “cheaper” or “dearer” to borrow. A rock-bottom interest rate allows corporate and individual borrowers to invest and acquire on the cheap. A higher effective interest rate tends to put the brakes on borrowing and overheated economic activity.

When the pandemic hit in the first quarter of 2020, the Fed dropped the short term interest rate to near zero. The rationale was that businesses and individuals would need capital to stay afloat, pay workers, and make it through hibernation.

Why doesn’t the Fed always keep interest rates this low? Three of the big negative consequences to doing so are:

- They hurt fixed-income investors looking for low-risk investments, particularly seniors. When was the last time you bought a Certificate of Deposit? CapitalOne offers a 5-year CD at 1% per year. Any takers?)

- It can overheat an economy, leading to inflation.

- Too-low interest rates can encourage over-leverage and lead to bubbles which pop.

Warren Buffett once spoke to my section at business school, and a classmate of mine asked him about the leveraged buyout (LBO) craze of the early 90’s. Buffett responded “Debt can be good, and debt can be bad. I like to think about debt akin the following proposition: I’ll pay you $20,000 to mount a sharp dagger on your car’s steering wheel. If you think you’ll only be driving on smooth roads, you’ll take that bet. But if you don’t…”

By the way, LBO’s still exist, and are simply called “private equity” now. Private equity firms basically amass capital on the cheap, then buy out companies, ramping up debt, and hoping and expecting to pay for their investment several times over by better operations and higher multiples.

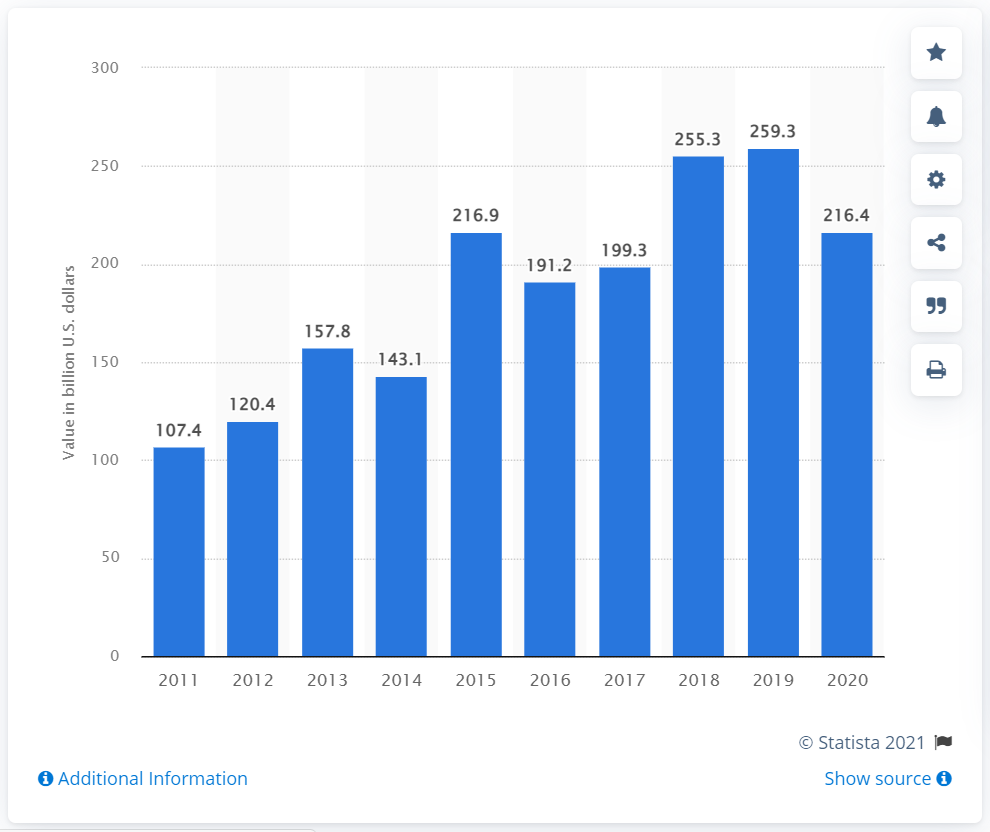

And even through the pandemic, these deals continue to motor along: “Private Equity is Smashing Records with Multi-Billion M&A Deals“, Bloomberg, September 2021.

Source: Statista

Meanwhile, Congress authorizes spending, and they’ve passed two measures during the pandemic, from the first stimulus during the Trump administration to the bipartisan infrastructure deal signed into law on November 15th, 2021.

Where to from here?

It compounds problems for Dems; high inflation is political poison for the party in office. Not only is a weakened budget highly unpopular (duh!), but high inflation will accentuate a major philosophical divide in the party between its two major factions. Progressives and Moderate Democrats have very different economic films playing in their minds about how economies work or do not work. The progressive wing favors a path which involves more government largesse for struggling families — yet more spending on top of that already promised. They will also argue vehemently for continuation of eviction bans and imposition of rent-control in many cities. Yet at the same time, moderates like Senators Joe Manchin (WV) and Kristen Sinema (AZ) will interpret it as a clear signal that additional multi-trillion dollar federal spending is highly unwise, especially when we haven’t even fully spent the prior stimulus funds yet. Meanwhile, high gas and grocery prices are catnip for a sniping GOP; the attack ads are writing themselves with every fill-up.

The pressure is on the Fed to raise rates, which will make borrowing more expensive and often is stock-market bubble-bursting in nature. At a minimum, it will likely put the brakes on large-capital projects like factory-building, private equity M&A, home-buying and construction. In non-pandemic scenarios, the federal reserve’s typical reaction to the prospect of inflation would have been to raise interest rates by now. Hiking interest rates makes money “more expensive” to borrow, thus tapping the brakes on the economy. But thus far, the Fed has done nothing of the kind. However, interest rates will rise soon — in September 2021, the Fed signaled it could hike rates “six or seven times by the end of 2024,” and it’s expected to speed up the end of bond-buying (the “tapering” of its quantitative easing).

Passage of “Build Back Better” is now more at risk than ever. A solid argument can be mustered that we haven’t yet spent all the money from the two existing stimuli, and that the last thing we need is yet more borrowing and federal largesse. When your constituents are feeling price hikes everywhere, it’ll be easy for the opposition to make the case that trillions more spending shouldn’t happen. Inflation also erodes the political capital of the president, who repeatedly promised he’d “shutdown the virus, not the economy.”

Momentum will grow for a return to normalcy. High inflation during a pandemic places greater pressure on governors and the executive branch to justify the potential economic impacts of intervention. But it’s fraught with conflict, because we don’t have a shared vision of how to best respond. While Reagan made hay of “stagflation” of the Carter era to win in a landslide in 1980, we should recall that the enemies were mostly outside our border: OPEC and the Iran Hostage Crisis were unifying to Americans. Today, we face inflation with wildly varying strategies, and nothing close to national consensus or unity. The GOP is rather unified that a highly interventionist stance toward COVID should end, but within the Democrat party, there are wildly varying views as to how to best respond.

This is likely to make a divided society even more divided. Unlike the 70’s, when OPEC and Iran presented us with easy, unifying foes, people are arriving at different diagnoses of how we got here, and which dragon needs slaying.

Today, major institutions like Governors, Congress, teacher unions, and the press are viewing the pandemic through very different lenses. It is harder than ever to get to a national consensus as to how to best respond. We were told for months that inflation is transitory, but now are told that it doesn’t really matter what you call it. We are told even that inflation is somehow good. Senator Elizabeth Warren casts inflation primarily as an oligopoly problem (looking at you, Big Chicken) and clamors for trillions more federal subsidy to Americans. Other leaders in her own party think a strategic pause in stimulus spending is in order. And the Republicans, out-of-power, have it easy. They need only hawk t-shirts festooned with a fuel pump and “Let’s Go, Brandon.”

For me, I think it’s time to recognize the connection between our responses to the pandemic and the economic impact on millions of Americans. Public policymaking is about resource allocation and minimizing harm. We have been extremely focused at one type of harm, but not broad-eyed enough at multiple types of harm. Let’s face it: COVID-zero is not going to happen. The virus and its variants are now endemic. I’m not saying we need to throw caution to the wind — sensible measures are still in order — but we need to have a much better sense of how elevating fear and continually teasing more remote schooling, and more labor-pool-restricting mandates have major impacts on our society.

We now — mercifully, miraculously — have vaccines and antivirals, and we can and should protect the vulnerable. But society itself should seek to return to normalcy.

Putting aside vaccination, which clearly help reduce the worst outcomes (hospitalization and mortality), it’s actually rather difficult to muster a case the interventions we’ve taken have been incredibly effective and linked to reductions in per-capita hospitalization or mortality, when you compare intervention regimes across the states. Democrats, in particular, seem very unwilling to let that reality sink in, and if they don’t change course soon, they will likely see what happened in Virginia last month on a national scale, come November 2022.

Public policy is about resource allocation and tradeoffs. Doing more of A often means you get less of B. In a pandemic, resource allocation is ideally driven with a framework (yes, a very subjective one) about the best way to reduce overall expected harm. At the beginning of the pandemic, we had massively wide “beta” on what the expected harm might be. Two years on, with vaccines and antivirals, and knowledge of the relative weakness of efficacy of non-pharma interventions, we should turn our attention to other harms we are imposing in the calculus.

In the state of Florida, we have Governor Ron DeSantis pushing back on vaccine and mask mandates. Yet in New York, we have Governor Hochul issuing statewide edicts which foreclose all elective surgery. Those of us who believe that we are reaching — or have already reached — the endemic stage of COVID favor a quicker return to normalcy, or at least clear offramps as to when we will be able to do so. Businesses and schools plan on long-lead time. It’s important that the metrics be stated, and there’s no excuse that they not be. The public and media don’t even seem to be demanding off-ramp metrics.

Thus far, we don’t even have the off-ramps, and there’s a huge psychological impact to that. If you’re a parent of a K-12 student in a blue state, you know intimately what I’m talking about. It’s time for us to get clear on when we can move on from a crouch. Some of us believe that the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI’s) we’ve imposed, which include remote schooling, lockdowns, supply chain headaches, workforce reductions, forced masking for K-12’ers, concomitant mental health crises, lack of childcare, etc. are now imposing far more collective harm than we can justify. There is little clear connection to reduced hospitalization or death with respect to these interventions. What evidence does exist might have been justifiable in a period of so much fear, but we are now a bit smarter, and should update our priors, and think more broadly about total societal harm, and ways to reduce it.

The Democrats best hope is that some leader emerges to make such a case, before the November fate is sealed. But they will have a heavy lift. They’ll have to bring most of the party, and the media, to that entirely new mindset, or at least remind them that a return to normalcy is a big part of what they actually ran on last year, before a surprise win of all three branches of government in the Georgia Senate runoffs filled their eyes with visions of sugarplum.