Computer Science legend Donald Knuth once said: “premature optimization is the root of all evil.” What did he mean by that? In his paper Structured Programming With Go To Statements, he elaborates:

Programmers waste enormous amounts of time thinking about, or worrying about, the speed of noncritical parts of their programs, and these attempts at efficiency actually have a strong negative impact when debugging and maintenance are considered. We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%.

Donald Knuth, Structured Programming with Go To Statement

There is a time and a place to worry about small efficiency gains. The vast majority of times, these gains are swamped by problems they bring in implementation.

What does this have to do with vaccine distribution? In practically every major state, I’m reading about shortfalls of vaccine delivery in the last mile. For instance, Washington State, California, New York, Ohio, Texas and elsewhere.

Could it be that we are trying to optimize the wrong thing?

We Are Wasting Time and Risking Lives with Focus on Small Efficiencies

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, the curious leader who’s been elevated, both by himself and a fawning media to undeserved hero status, has trotted out diktat after diktat of late. One needs a news ticker and custom Google Alerts to keep up with them all.

In the past two weeks alone, he’s put forward an Executive Order to fine doctors, nurses and other healthcare providers $1 million if they facilitate jumping the COVID-19 vaccine line, and publicly threatened them with permanent loss of their license. A few days later he followed it up with a threat to fine hospitals $100,000 and terminate their vaccine access if they don’t use up their supplies within a week. I don’t think he’s being intentionally malicious — he truly thinks he’s doing the right thing here.

But while it may serve as an ego boost for him and satisfy thirsts for command economy experiments, it’s head-spinning just how oppositional these are to the basic goals he should have. Goals for sensible leaders in this crisis should be to reduce friction, instill confidence, eradicate logistical bottlenecks, and get vaccines out to people, particularly the elderly, quickly.

CDC Prioritization Framework

In a more orderly way, this autumn (and why did it wait so long?), the CDC convened a workgroup to study the best Phased Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccines, and rightly states the key policy question as “Which groups should be offered COVID-19 vaccination in Phase 1B and 1C?”

The 40+ slide deck includes a whole lot of counterbalancing tradeoff questions:

02-COVID-DoolingWhile I appreciate the nuance and laudable academic intent, I think it’s lost the forest for the trees. On slides 37 and 38, you can see the payoff: the CDC is not recommending an age-based framework; it’s saying “frontline essential workers” should come before those who are 75+. I’m arguing with that workgroup conclusion; I think it’s suboptimal (as does Israel, below.)

Simplicity matters. In fact, it matters a ton.

Simple Beats Complex Nearly Every Day

To Andrew Cuomo, I’d say that while would-be line-jumpers — including the wealthy, powerful, and connected — certainly deserve all the social scorn for taking the places of people more deserving, there is no evidence, nor even anecdotal stories, that supply constraints are due primarily or even partly to line-jumpers.

In fact, we currently have the quite opposite problems, including (a) last mile distribution logistics, (b) pernicious lack of public trust in the vaccine which at times appears to be growing, (c) poor centralized oversight, (d) vaccines going bad before finding an arm, (e) general risk aversion, and more.

In other words, we are overoptimizing solutions for problems that do not exist.

This goes for leaders and we in the public, and the media. I was struck by this CNN “journalist’s” interchange, who clearly thought she was the heroine in her own story, and felt the framing preamble she put a lot of time into in her “question” was far more important than the answer:

The reasons why it’s come to this halting last-mile delivery across America are myriad. But I think chief among them are complexity and perceived risk. I’ll talk about complexity in a moment.

But perceived risk is a fierce enemy here, and leaders should seek to stomp it out. By perceived risk, I mean both (a) the perceived risk in taking the vaccine (i.e., counteracting this perception should be a clear focus in public messaging by leaders and media), and (b) the personal or career risk they feel are taking by being “outed” for inadvertently or even intentionally falling short of a diktat.

We live in the age of the example-made, the cancellable. In that environment, people are gun-shy about stepping up in line, even when it’s their turn, if the verification regime is squishy and the “rule breakers,” knowing or unknowing, are elevated in disgrace. You see this kind of caution even in noble actors like the incomparable Dolly Parton, who refused to get the vaccine even when it was her turn, just because she didn’t want others thinking ill of her. Very noble intent, but it’s not the effect we should want, nor I think the optimal signal to send.

Do we really want to make people feel more at risk of becoming the next public example?

Further, those on the other end of the needle — i.e., those in healthcare and public policy who are in charge of the vaccine last mile distribution — don’t need more risk to worry about. They need simplicity, logistics help, risk reduction, and support.

Understandably, they won’t want to become the next example in a news cycle gone mad. For anyone perceiving high personal risk, waiting and caution are rational decisions, even when it’s their turn.

Leaders like Andrew Cuomo are playing right into that fear.

What the Hell Are We Doing?

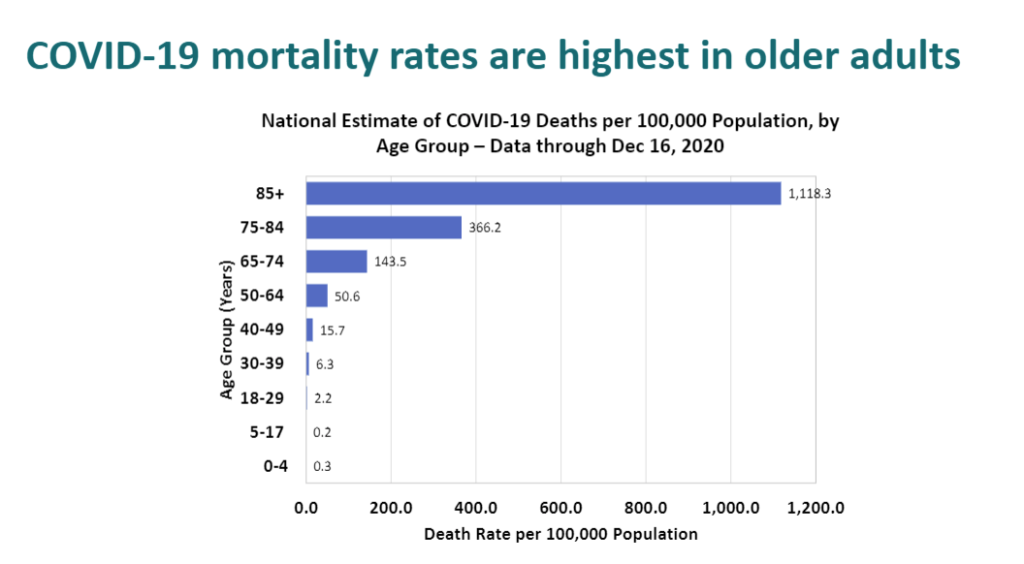

What has all this lockdown sacrifice been for, if not to protect the lives of those most at risk? And those most at risk, by far, are those 70+ and those with comorbidities.

Some are joining teachers unions and using COVID as a social justice leveling opportunity, suggesting that vaccines shouldn’t go first to the elderly, because the elderly, through no fault of their own, apparently skew whiter. Listen to Dr. Harald Schmidt to the New York Times a couple weeks ago:

“Older populations are whiter. Society is structured in a way that enables them to live longer. Instead of giving additional health benefits to those who already had more of them, we can start to level the playing field a bit.”

Harald Schmidt, Professor of Ethics and Health Policy at University of Pennsylvania, in the NYT

That’s entirely the wrong direction, in my view, and it runs counter to the entire philosophy and messaging driving the lockdowns about protecting those most at risk. And you know you’ve got a problem if you change “white” to “black” in some sweeping statement, and could easily imagine the resultant utterances coming from a Grand Wizard of the KKK.

Let’s use actuaries and doctors for what they’ve trained, and let’s only start freaking out when there are huge denials of delivery due to major shortages. (Related: why is the present-era instinct that to achieve equity, we must always level down? Why not emphasize that all those with comorbidities should be welcome and encouraged? There’s ample data that shows that those with Vitamin D deficiency, high diabetes and obesity incidents are at much higher mortal risk. Those who are — of any identity group or accident of birth — should absolutely jump ahead in line!)

Today, I’m reading too many stories about vaccines going bad before they find an arm. That is evidence of a different kind of problem.

Simplicity Is Always a Force Multiplier

“Perfection is Achieved Not When There Is Nothing More to Add, But When There Is Nothing Left to Take Away”

Antoine de Saint-Exupery

The best designers know that exception-based user-experiences are suboptimal.

What Would a Simple Framework Look Like?

Maybe we could focus on all those over 70, go by birth year, allow those who have demonstrated health record of comorbidity participate in any age group? Maybe we could go upward by decade, starting with those born prior to 1930 for duration X, then 1940 for duration Y, then 1950 duration Z, etc?

Age cohort is a dramatically more easily verifiable, actionable, message-able approach. The time and dollars saved could be put where it needs to be.

And let’s give discretion and deference to those who’ve invested a substantial part of their lives to care for people — the doctors and nurses and nurse-practitioners. Yes, there will be some mistakes. But isn’t the least we can do, after all their many sacrifices, to say “we still trust you to make the right call?”

CDC’s Priorization Framework

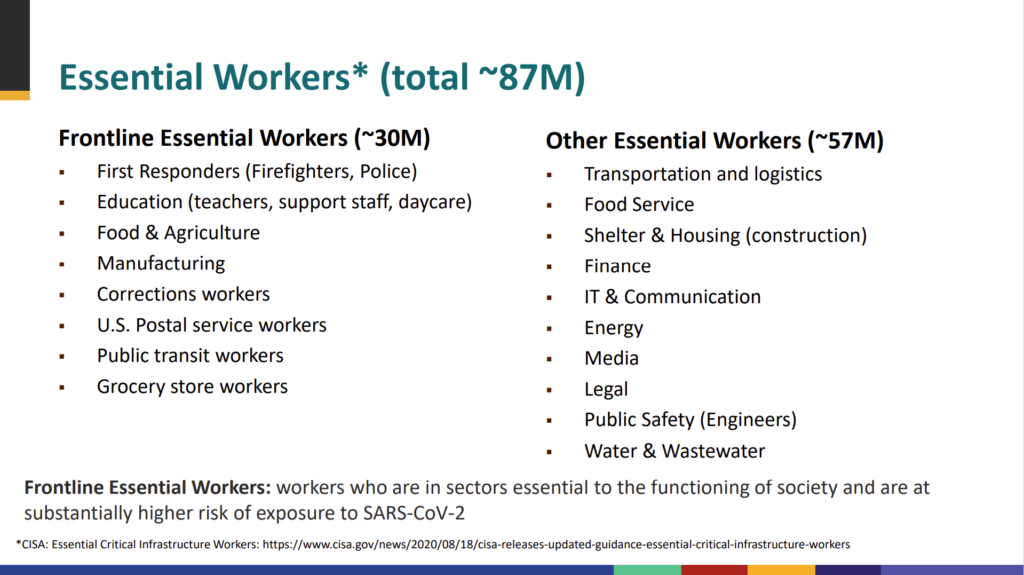

For its part, the CDC attempted to enumerate the group of essential workers, and it’s enormous — about 87,000,000 Americans fall into that category.

Should a healthy 30 year-old pharmaceutical rep (a “healthcare worker”) get a vaccine before a 75 year old? Should a 25 year old waiter or back-office employee at a restaurant (a “food service worker”) come before an octogenarian? I don’t think so, in any sensible world.

If you had one axis and one axis only by which to determine rate of mortality it’s clearly age. That’s the high-order bit. Those over the age of 70 are at high mortal risk; those younger than 70 generally are not.

In implementation, simplicity matters. And just how do we validate complex frameworks, especially when they have Cuomo-like penalties if, God forbid, in our nation of 328 million people, anyone gets it wrong? What costs are involved in monitoring compliance? What time is taken from other actions? What’s the opportunity cost?

From a practicality standpoint, how easy is it to verify the status of “essential” worker? Do you ask for employment records? Should every vaccination have the friction of verification? We are talking about over 400 million injections in America alone. Every possible inefficiency should be stripped of unnecessary complexity.

What We Can Learn from Israel

In Israel, they’ve taken a radically different approach. I love their approach. And their results speak for themselves: at this writing, they’ve already vaccinated the majority of their population over the age of 60.

What are they doing that’s different?

For one, they’re doing it by birth year. Easy to communicate. Easy to verify. Easy to deliver.

Logistically, they’ve made it simple. They’ve set up drive-throughs.

They’ve made it participatory. If you bring someone elderly to get vaccinated, they also offer to vaccinate you, just as a thank-you.

This kind of simplicity also allows them to keep their focus on the customer/patient. There’s this nice touch, told by someone who experienced it:

Still, I was momentarily confused as we waited the required 15 minutes after the shot before leaving, as staff members walked around handing out copies of little booklets. “Games for children?” they asked quietly, offering people as many copies as they wanted. “What on earth are these for?” I wondered. “We’re not vaccinating kids, it’s nighttime and there isn’t a kid in sight. Except for the staff we’re all over 60. Who needs kids’ games?”

Vaccination Miracle Brings Israel Back to Its Roots, Daniel Gordis, Bloomberg Opinion

And then it struck me, as people happily and gratefully took copies of the booklet — and then asked for another copy or two. The booklets weren’t for us — they were for our grandchildren. The HMO intuited why so many of us were there that night; we hadn’t hugged our grandchildren in almost nine months. Obviously, we were also relieved to reduce the possibility of getting sick, but somebody in an office somewhere, far from the arena, understood instinctively who would be getting on line first, and why.

When I was at Harvard Business School, I had a consumer marketing professor who would frequently say “Let’s push the grocery cart down the aisle. Tell me that story.” What he meant by that, of course was to put yourself in the shoes of your target, and tell the story — know the story — of what precedes it, what happens during that moment, and what follows. He was relentless about not making it just a platitude; he wanted you to literally tell the story of the life of that person, and the moment in the store, and why it mattered to them.

Putting oneself in another’s shoes can be a platitude, or it can be an opportunity for real insight, if you really dig in.

Here, I think most states in America in general are prematurely attempting to optimize vaccine delivery, bringing with such an approach all kinds of side-effect and supply chain problems.

When boxes upon boxes of soon-to-expire vaccines are there staring at the physicians and nurses in a hospital or HMO, do we really want them thinking about the risk of a $1 million fine and loss of their license if they inevitably make a mistake, or someone knowingly or unknowingly misrepresents their position in line?

Or would we rather not have the perfect be the enemy of the good? I vote the latter. We should prepare the public for there being cases where it won’t be perfect. We should be encouraging people to queue by age. We should use birth year and make it super-clear, allowing for frontline workers or others who truly believe themselves at risk due to comorbidity or work to show up for “stand by” delivery that day.

In short, I think we should follow Israel’s example.

A birth certificate or drivers license should be sufficient to prove you’re entitled to a vaccine now. And sure, additional exceptions could be made at the delivery level, by the very people who chose healthcare for a profession, earned a graduate degree in it, and have been practicing for years. Let’s not let the attempt to right every wrong and ingest every nuance so complicate the delivery that we lose valuable time, and lives.