In a clear sign that the Administration is anxious about Thursday’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) report from the Commerce Department, the White House is making an all-out push this week around what constitutes a “recession.”

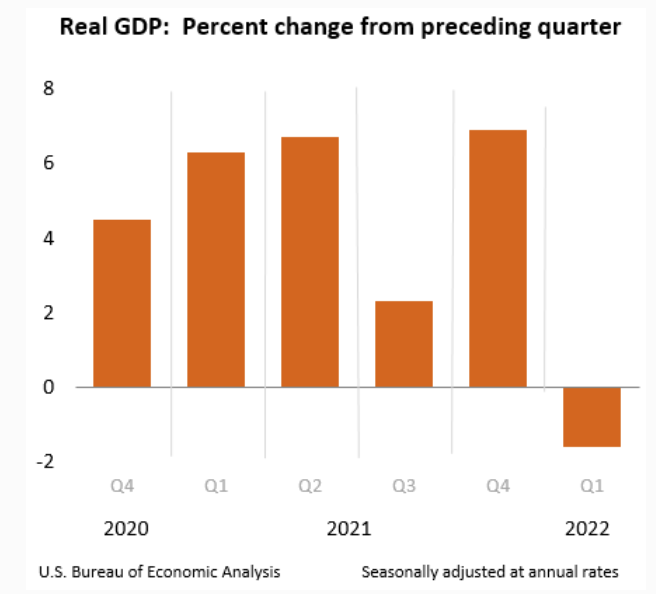

While it’s true there is no single steadfast criterion for a recession, by far the most common indicator used for recession has been two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP.) That’s the accepted shorthand criterion that MBA students like me were taught in our macroeconomics classes. You’ll find it in many economic textbooks, investment dictionaries, and nightly news segments.

And there’s the rub, because the US GDP declined in the first quarter by 1.6%, and signs are pointing to a decline again in the second quarter:

No politician wants to go into midterms in a recession.

Beyond purely political motivations, naming the beast can plausibly make it worse. That’s because when consumers feel anxious about future employment or wage prospects, they may postpone durable goods orders and cut down spending to the bare essentials. Ditto for corporate boards: as soon as they decide a contraction is here, many will rationally postpone investment and cut back hiring. Chief Executives of Bank of America and Goldman Sachs have each decided that a recession is likely here.

On Thursday, the White House began an effort to get out in front of the Thursday report, releasing How Do Economists Determine Whether the Economy is In a Recession? on the official White House blog. They note that the official recession scorekeeper is the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which defines it as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.” But there appears to be no statutory language that officially makes NBER the umpire. It’s a subjective term which has a long-accepted criterion, and the White House is arguing for a softer definition.

Clearly, Democrats do not wish to head into the midterm elections in an official “recession.” To that end, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was dispatched to Sunday news shows and downplayed the risk of recession, arguing that consumer spending is growing, that the economy has added an estimated 400,000 jobs, and still has a relatively low unemployment rate of just 3.6%.

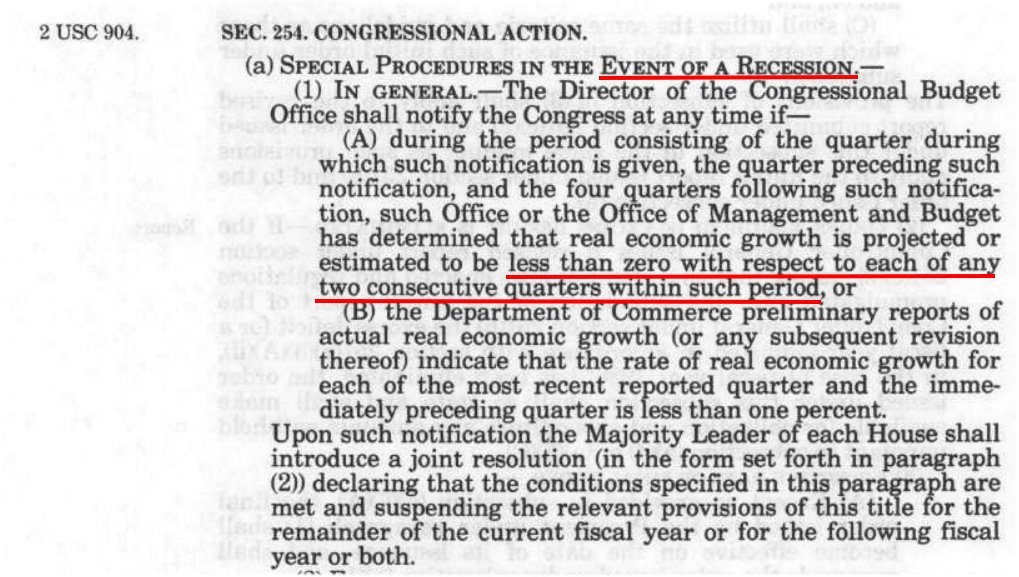

Congress? They use the 2-Quarter Definition.

Interestingly, a definition of recession actually does exist in statutory code passed by Congress, in the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act of 1985. It adopts the two-consecutive quarter definition:

Warning Signs

Regardless of what we call it when, there are several economic warning signs.

Inflation, of course, is the metric that everyone feels every time they visit the grocery store. Inflation rose 9.1% year over year in June, which is the highest year over year increase in 40 years. Seattle-area prices are on an even bigger tear, jumping 10.1% since last year.

To try to get a handle on inflation, the Federal Reserve has been steadily hiking interest rates, which tends to slow demand. The slowing of demand typically relieves upward price pressure. But the Fed wants to hit the brakes without slowing it so much that it turns the economy into full-blown recession.

This is extremely challenging, because soaring inflation isn’t solely due to Fed actions, but also to factors out of their control, like disrupted supply chains which have caused scarcity of some key goods, the war in Ukraine, energy and particularly refinery constraints and capacity reductions, the trillions poured into the economy through the American Rescue Plan, and more. Inflation, in short, has many fathers.

The Federal Open Market Committee continues to raise interest rates, and the Federal Reserve is tightening access to money, signaling that still more is likely ahead. This does tend to put the brakes on growth, as money itself becomes more expensive to borrow or acquire.

The White House is leaning on “strong labor market” as its main justification as to why we’re not really in a recession.

Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre tackled this question today, again emphasizing the “strength” of the labor market:

But specifically on the hiring front, it’s a very interesting and mixed picture. The topline number of employment looks good at first glance. But while labor shortages exist in many essential roles (often lower-wage), the precise opposite appears to be true at the higher end of the wage spectrum.

Seattle presently has critical staff shortages in essential workers, particularly in public safety (police, firefighters, healthcare workers), and also ferry workers, teachers and more. But growth in high-wage, high-tech knowledge-worker hiring is seeing a significant slowdown. In the past three months, tech firms like Microsoft and Google have announced slower hirings. Layoffs at startups appear to be growing. Apple, Meta, Uber and Amazon have also joined the list. Venture funding of early-stage startups (Series A and B rounds) was down about 22% year over year in the second quarter, according to Pitchbook.

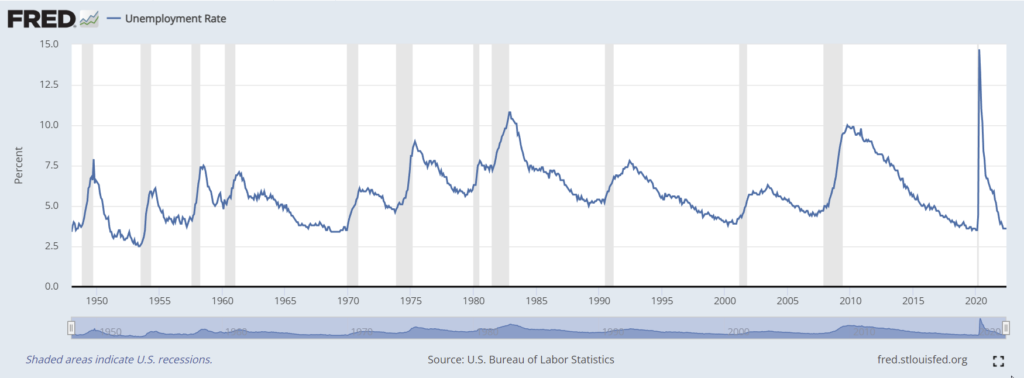

Yellen and Jean-Pierre remind us that the nation’s overall unemployment rate is low, as can be seen in this chart from the St. Louis Federal Reserve:

But the “low unemployment rate” masks a lot. The picture is far more complex, and less rosy than such a chart might initially suggest. That’s because overall unemployment measures the percentage of people in the workforce or seeking to be in the workforce who are unemployed, but the labor force participation rate (i.e., the percentage of all Americans who are in the workforce) must also be considered to get a true picture of America’s current workforce trends.

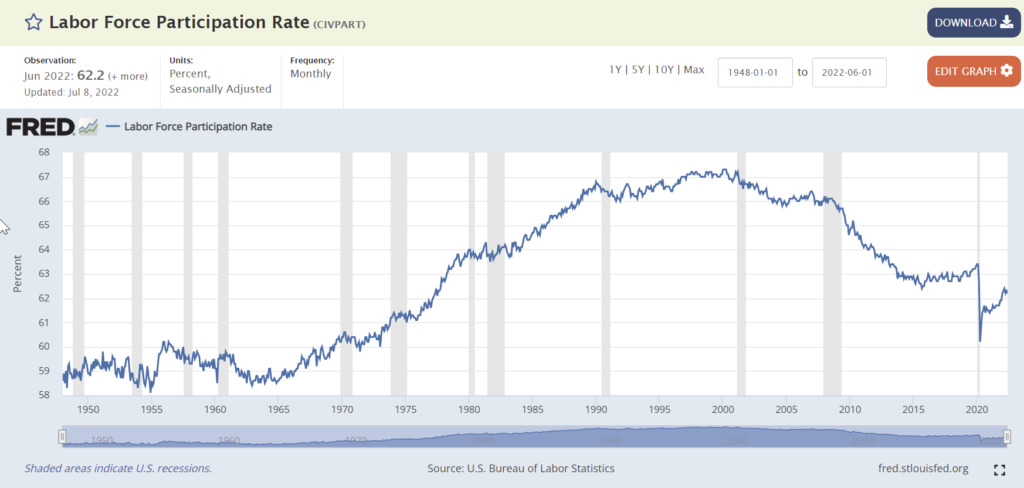

Looking at the labor force participation rate, notice that the pandemic brought a “Great Resignation,” and many Americans — particularly those in essential jobs (e.g., healthcare hospital workers, firefighters, teachers, warehouse workers, retail) still haven’t rejoined the workforce:

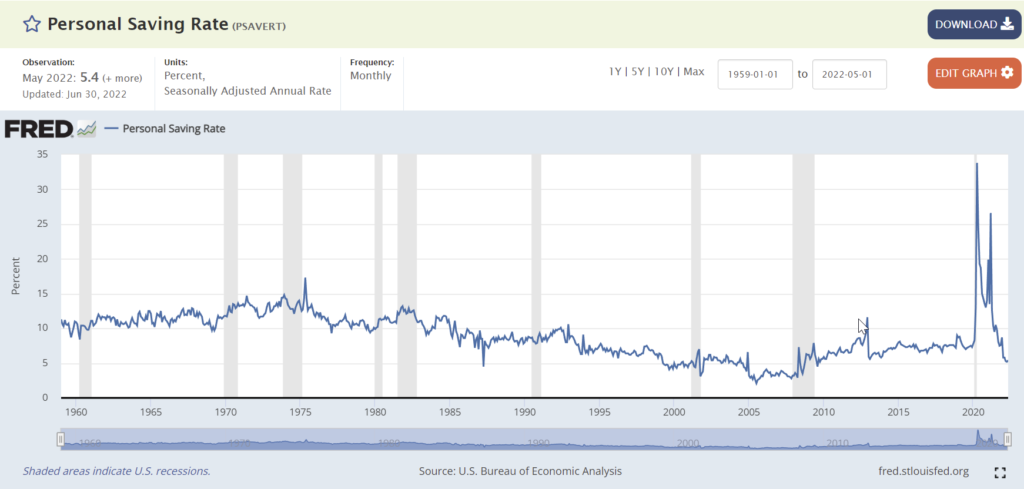

The noticeable decline in workforce participation rate suggests that people have been living off of household savings. And indeed, that appears to be the case:

These charts tell a story: many opted out of the workforce and have been living off of savings and/or asset appreciation. But these savings are usually tied to assets (stocks, bonds, home valuation etc.) which are likely to deflate as the economy contracts. One of the key risks that doesn’t get enough attention is that it may be very challenging for millions of Americans to try to re-enter the workforce during an economic downturn once they hit the end of their savings.

Is the “let’s talk about the definition of recession” simply a good-faith effort to introduce nuance back into the American political conversation, and curtail an even worse downturn by not naming it? Or is it a cynical attempt to sweep a major political liability under the rug by redefining a long-accepted word? I’ll let you decide.

I’ll be sticking to the colloquial definition of recession — two or more consecutive quarters of negative GDP. But we should recognize that this is likely to be a recession with very unique characteristics, and won’t be easily mapped to recent ones.