Note (July 2020): This post is a compendium of links, resources and commentary related to the proposed cutting-by-half of the Seattle Police Department budget. Like the rapidly-building “plan” itself, this article is pretty scattered and incomplete, and meant to be a holding tank of relevant articles, resources and perspectives to consider when developing your own view on the topic. It will be updated over time.

It is not intended to be one-sided. So feel free to suggest new Seattle-specific resources and links to me via Twitter, especially those which disagree with mine. If they better inform outsiders, ideally with concrete data, I’ll do my best to work them in.

In general, my own views are: supportive of police reform, supportive of more transparency and oversight, yet opposed to a 50% cut being the way to drive it. Rather, I’m in favor of defining success metrics that matter to all Seattleites, letting those drive the reform plan, rather than a top-down “let’s cut 50%, allocate a bunch of money to this or that organization, and figure it out” kind of approach. Seattle has a terrible record of doling out funds to third party service providers; so little accountability, so little check-ins, audits, definitions of success metrics, and ongoing measurement. The result has largely been paydays for third-party service providers, who, once entrenched, are rather difficult to see into.

I also feel improved public safety outcomes cannot also arrive without serious inquiry into the judicial (i.e., post-arrest) system that all too often lets frequent offenders cycle through the system without treatment, has a myriad abuses of freedom and liberties, doesn’t address mental health or addiction properly, and imposes too few consequences for repeat offender actions which truly harm others. The process of success metric definition need not be a long one, but it should be inclusive, and take into account the public safety needs of all Seattle dwellers, renters, owners, service and businesspeople, all identity groups, etc.

“Laws without enforcement

Abraham Lincoln

are just good advice.”

Law enforcement has been essential in every society. Seattle’s own history with policing is a varied and checkered one, recently involving a federal consent decree, strong crackdowns on protests, some recent success in diversifying its workforce, leadership appointment political battles, worsening morale and staffing problems, a highly contentious and long-drawn-out battle over renewing the police union “SPOG” contract, increased militarization, claims of targeting and racial profiling, and fierce allegations by activists that the Seattle Police Department (SPD) both represents and perpetuates institutional, systemic racism.

- Brief overview of the federal Consent Decree, 2012, King5 NBC News

- Links to Consent Decree and overview from Civil Rights Division of DOJ http://www.seattlemonitor.com/overview/

- Appointment of Carmen Best, Police Chief (Seattle Times, July 18 2018)

Fast-forward to 2020

2020 has involved these distinct, contentious events:

- January 23: shooting downtown at Westlake (7 injured, one dead)

- COVID-19 and first-responder response/support

- George Floyd’s murder and protests, and the larger Black Lives Matter Movement

- Expulsion of Seattle’s Police Union from the Labor Council

- CHAZ/CHOP protest/takeover on Capitol Hill

- Resultant awareness and public safety challenges — 5 shootings, property damage

- Elevation of Seattle as a storyline in major media outlets

- Ongoing rhetorical battles between national and mayoral leaders

- Marches on the Mayor’s personal home

- Tragic killing of a BLM protestor on I-5

- Resignation of Police Chief Carmen Best

- Record number of Seattle Police Officers leaving the force

- Incredible lack of knowledge demonstrated by City Council members in charge of the restructuring

- Increasing crime (homicides in particular have now crossed a ten-year high, in 2020)

One of the most central milestones was City Council’s vote indicating support for…

50% Cut in SPD Budget

Seattle’s City Council is a 9-member body that sets the laws of the city of Seattle. It now has a veto-proof majority of 7 of 9 councilmembers to cut the Seattle Police Department Budget by 50%, a goal long sought by some of the most leftward voices in the City. It gained increased calls in 2020, particularly in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota.

City Council’s decision to slash 50% of the budget is, at present (July-October), without any bottoms-up plan or even clear set of metrics which will constitute success.

Chief Best’s Thoughts

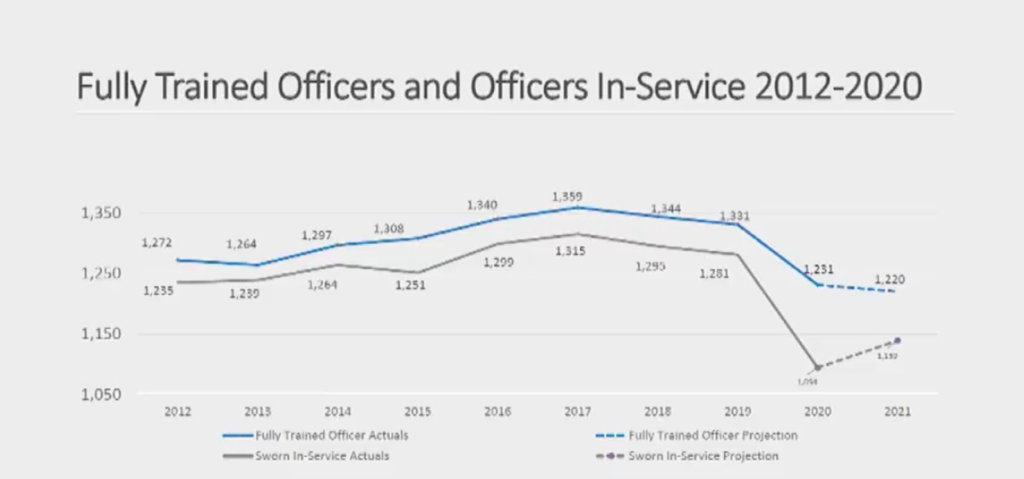

Police Chief Carmen Best published a video on July 10 2020, addressing the roughly 1,400 sworn Seattle Police Department officers under her command. There’s a companion memo, below, summarizing what SPD feels those cuts will likely mean:

Chief Best outlined some of the adjustments she feels the department would have to make with a 50% cut:

468745236-Mayor-Letter-Chief-Best-Council-Budget-ProposalSeniority May Well Result in a Less Diverse Force

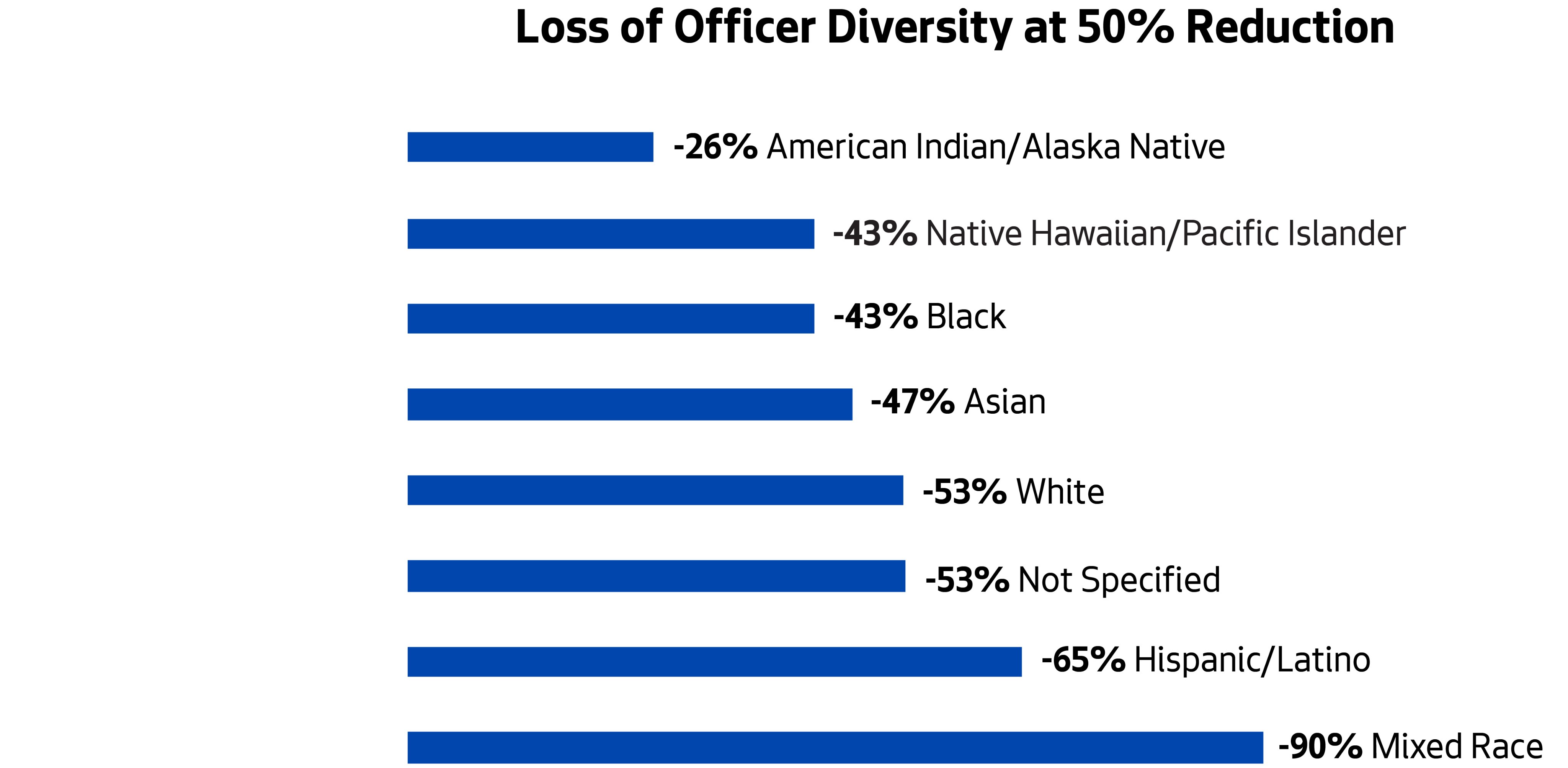

SPD notes that due to legally-binding union contracts signed by the City and the Seattle Police Officer Guild, the layoffs forced by these cuts would result in SPD becoming less diverse, at least in the short-run.

This claim was met with swift reaction from “defund” proponents on Twitter, including former Mayoral Candidate and attorney Nikkita Oliver:

[An aside. It just struck me that the two most forceful, clear and consistent advocates of the camps which will move this city in one major direction or another are two Black women. Progress worth noting?]

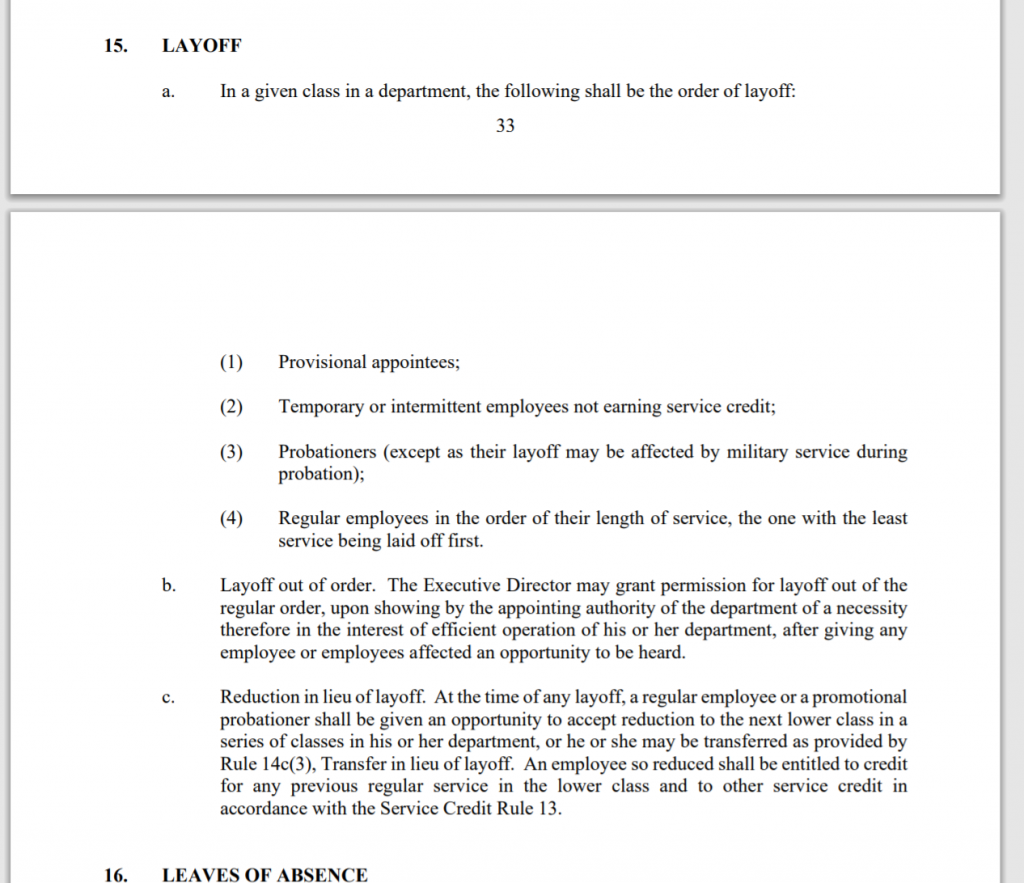

Council Member Lisa Herbold notes that it should be legally possible to lay-off out of order of seniority:

Here’s a link to the document that CM Herbold was referring to: Rules of Practice and Procedure. You’ll find the relevant piece on page 33, which indicates some other conditions:

Is there a risk that lawsuits will still be levied and lost? I think so. Worth taking? Perhaps.

Constitutional Law scholar Jonathan Turley outlines many ways in which this proposal may violate laws:

While [Herbold’s suggestion to fire based on racial makeup, out of order] would be the definition of racial discrimination, Herbold clearly believes that it is discrimination for a good cause. The federal courts are likely to disagree. Most notably, Herbold’s call for racial discrimination against white officers would seek to undue the work of Justice Thurgood Marshall who insisted that racial discrimination unlawful and evil regardless of the race you want to disenfranchise or discriminate against.

– Jonathan Turley, Seattle City Council Member Suggests Firing White Officers in Massive Reduction of Police Department

Public Disapproval

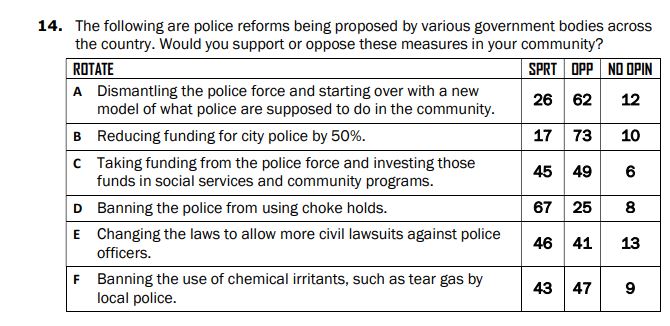

Crosscut/Elway is out with a new poll that shows 73% of respondents are opposed to reducing SPD funding by 50%:

Where does SPD’s money go today?

The Daily Hive has a pretty good rundown here:

https://dailyhive.com/seattle/seattle-police-department-funding-2020

Mayor Durkan’s Position

As is often the case, Mayor Durkan has been trying to strike a pragmatic middle, “kind of a lukewarm water between ‘fire’ and ‘ice'” as so memorably stated by Derek Smalls in Spinal Tap. She is still reeling from a very hard turn to the left by City Council from the November election, and hard-left activists flooding her inbox, and even, shamefully, her driveway.

But her reality — and the reality for us moderates and taxpayers is that there is considerable momentum to defund at least 50% of the SPD budget without any clear plan or measures for success.

And as Carmen Best notes, all this momentum now arrives at the doorstep of SPD, without much proactive input from the police department itself. At present, the Mayor’s Office seems to be trying to elide the COVID-related cuts with these funding cuts. I’d expect her to continue along this angle, attempting to preserve as much of the current makeup of SPD as possible:

But it will be a huge challenge.

On July 13th, the Mayor came out swinging, blasting the City Council’s plan:

https://crosscut.com/2020/07/durkan-hits-back-pledge-defund-seattle-pd-50

Legal Impediments

Kevin Schofield at SCCInsight has a must-read article on all the legal impediments to cutting the budget by 50%:

“Defunding SPD” is going to be a lot harder than anyone thinks

Where are the Guiding Metrics?

My biggest question — what will determine success or failure with such a drastic change? How will we know when we’re moving toward something better, or moving toward worse outcomes for the Seattle community as a whole?

The statement by 7 of 9 Council Members to support a 50% cut in police funding comes without a bottom-up plan, and without any metrics which will help us know if the changes made actually improve things or move them in the wrong direction.

“I have been struck, again and again, by how important measurement is to improving the human condition.”

Bill Gates

You cannot improve what you do not measure. You cannot even know whether you are improving at all without measuring.

And thus far, any measurements or metrics are wholly absent from the discussion.

It seems to me that good people can disagree about how to best achieve improved public safety and equity. But can’t we first try to establish agreement on, say, the Top 10 Signals for what constitutes better outcomes? If not, how will we know if we’re making progress or moving further away from our goals?

I think clearly, all citizens and leaders should want to reduce the rate of bias and unjust outcome. Do the public safety needs of all identity groups also matter? I assume they do. Most citizens do care about reducing assaults, robberies, addiction, homelessness and more.

I’ve asked Council members a few times, respectfully, what are the outcome metrics that they’ll be using to judge whether these changes are successful or not.

That is a very basic question.

Where is the Seattle press?

We need the press to ask City leaders what the plan is, and how they’ll measure success. Do City leaders have a mandate to do this 50% cut? Do citizens know what’s being proposed? Do leaders know how they’ll do it, and what will constitute success?

I’ve asked journalists like Dan Beekman of the Seattle Times, repeatedly, whether journalists will actually press Council members to answer these questions. No answer. For instance, this thread.

Silence, thus far.

And thus far, only one council member — Dan Strauss — has mentioned anything that could be considered a measure for success. It’s confined to 911, but it’s a start. His view is that the metrics for success are “Response times, and whether the people who arrive, 24×7, have the right resources to do the job effectively.” That’s a good start it seems to me, but those are the only measurable goal I’ve seen thus far in the entire discussion of these major changes. And I don’t quite know how we best measure “arrive having the right resources to do the job effectively.” (Do we do a followup survey? Who measures? Etc.)

Instead, the entire discussion to date has been driven by inputs to the program, as laid out in the four-point “plan” that 7 of 9 members have agreed to, in principle. It has the feel of a fight over both policy and money, with the latter sometimes taking precedence. Public safety seems to be taking a back seat in the dialog right now, at least the traditional measures of public safety (some typical measures listed below.)

“Decriminalize Seattle”

Take, for instance, the “4 Point Plan” being advocated by “Decriminalize Seattle” which is included in the PDF below.

Points 1-4 are entirely about inputs and allocations. None of these points include metrics for success, or a plan for who should own those metrics, how regularly they’ll be reported, and what we might do if we’re on the wrong (or right) tracks. As we’ve seen in the past, it matters whether there’s an interested agency reporting the numbers.

Presentation-Decriminalize-SeattleDecriminalize Seattle held a Zoom call “teach in”, which is available on Facebook but not embeddable here.

Good governance includes establishing what “success” looks like. Numbers are a key barometer of whether the new plan is getting closer to the goals, or further away from it.

Typical measures of public safety often include the metrics below. Anyone willing to go on record with predictions as measured in, say, three years? Reasonable metrics it seems to me include things like:

- Response times

- Violent crime rates (reported violent crime per capita)

- Property crime rates (reported property crime per capita)

- Whether those responding have the right resources to handle the situation effectively

- Officer-involved shootings

- Complaints against officers or SPD

- Assaults

- Shootings

- Recidivism

- Burglaries

- Gun ownership and purchase trends

- Gang activity

- Non-violent crime rates/conviction rates

- Homelessness counts

- Overdose deaths

Are there other key public safety, equity and public health outcome metrics that make sense to measure with numbers? What happens to “response times” when the agency is under entirely different leadership, and how should they be measured? Should they be independently verified? What do we anticipate about the directionality of these metrics down in let’s say, three years from now?

Are you personally directionally optimistic in these metrics, neutral or pessimistic?

The Challenge of Repeat Offenders

Last year, two blockbuster reports came out profiling Seattle’s most prolific offenders. System Failure Parts I and II.

Just 100 individuals accounted for 3,562 bookings in the State of Washington. About 9 months later, a follow-up report showed that these same individuals accounted for another 117 bookings. It also found that the City Attorney’s office only filed charges in 54 percent of the non-traffic criminal cases brought to it by the police, meaning, 46% of the time, they didn’t file charges in such cases.

system-failure-prolific-offender-report-feb-2019 System-Failure-Part-2-Declines-Delays-and-Dismissals-Sept-2019It also found that on average, it takes about a half a year for the City Attorney’s office to file charges once the suspect is arrested, and nearly 2/3rds of a year in the case of assault.

Will Council Live By Their Own Decree?

Minneapolis’ City Council members who voted to “defund” the police about a month ago. And they quickly then voted themselves their own private security, at a cost to taxpayers of $63,000.

In Seattle, one council member signaling her support for a 50% cut in SPD forces is Council Member Lisa Herbold, who last year was quick to use her position to call not just the police’s 911 line, but the Chief of Police herself when she suspected, wrongly, that a mobile home was parked in front of her home to troll her.

Does she plan to go through Community Service workers in the new world or civilian 911, or make use of other channels? And will Mayor Durkan hold equal concern when personal property of others is violated as though it were her own?

“Decriminalize Seattle” Zoom Conference

A key set of players driving this conversation comprise a group called “Decriminalize Seattle.”

No question, their voices, just as others, are very important to hear in the process. Their lens is an emphasis on racial equity, many of the goals of the Black Lives Matter movement, funding affordable housing and more.

Given the rather large influence the group is currently having over major public safety decisions in the City of Seattle, it would be helpful to have an understanding of what kinds of public safety credentials and experience are represented by the group, and which cities of any size have adopted such plans, as well as their results. It includes groups like the Seattle People’s Party, Asians for Black Lives, the CID Coalition, La Resistencia, Trans Women of Color Solidarity Network, No Youth Jail, and more than 200 other organizations. What kinds of credentials in public safety and health policy, and what results of the collective group?

To be clear, my own public safety credentials are nil. They are nonexistent. But then again, I’m also not the one pushing a plan to reshape Seattle’s entire approach to public safety and cut the budget for the law enforcement organization of the city in half. I’m calling upon us to have metrics that guide our success, and I’m calling upon journalists to start asking that question of our leaders.

Has this combined group’s novel approaches been implemented, at scale, in cities of any size? If so, great! Let’s hear more about that experience and what we can learn. What can we learn from what works and what doesn’t? And if not, if we are truly donning the labcoats here, shouldn’t we know it? Isn’t that something that might make headline-level at The Seattle Times? What harm is there in bringing that fact to the attention of the public? And if true, isn’t it then ever more important to establish the metrics for success?

You can see a ZOOM call of a recent virtual meeting with council members and the Decriminalize Seattle group here:

CM González on “Defunding”

In recent days, Council President González has apologized for supporting police budget increases in past years, saying she no longer believes the department can be wholly reformed.

Oath of Office

Some, like Chief Best, are questioning whether a 50% cut in SPD is consistent with Council Members’ sworn oath of office. Curious, I tried to make the connection as to what they’re alleging.

All City Council members, when sworn in, take an oath to uphold the City Charter. See the 11 minute mark, for instance, for CM Herbold’s swearing-in ceremony, for instance, below.

Now, the preamble of the Charter of the City of Seattle, says very clearly:

“Under authority conferred by the Constitution of the State of Washington, the People of the City of Seattle enact this Charter as the Law of the City for the purpose of protecting and enhancing the health, safety, environment, and general welfare of the people…”

Charter of the City of Seattle

I think reasonable people can disagree about the right way to ensure health and safety of a citizenry. And “Decriminalize Seattle” has certainly stated their desires to enhance health and safety.

But notably absent so far from the “Let’s cut the SPD budget by 50%” movement have been any kind of metrics around public safety and health, merely (a) adjustments to INPUTS and policies, (b) hopes that by making these changes, we will achieve better equity and outcomes and (c) claims that SPD is unfixable/irretrievably broken and needs to be entirely reimagined.

How will we know if we are making improvements? How will Council Members know if they’re truly upholding their oaths to ensure better safety and health?

Morale Crisis at SPD

Meanwhile, even prior to this, there was a growing crisis of morale at the Seattle Police Department.

“Culture is toxic; morale is low”: Survey of Seattle Police officers paints bleak picture, Crosscut

Speak Out Seattle, a public-safety advocacy group which I volunteered for last year, chiefly by livestreaming their City Council forums, put out a video a year ago on the Seattle Police Officer morale crisis, and how Seattle’s staffing levels compare to other cities. I share it below because the comparative figures at the end are I think worth noting in the context of this discussion:

The crisis appears to be accelerating:

Finally, is all this premised upon real, or imagined human behavior?

As I wrote back in November, I really hope the human behavior that the current majority of City Council members imagines actually exists in real life. Because from that, all else follows.

- Is compassion the same as lenience?

- Are unarmed community service workers better at diffusing, say, assaults and domestic violence?

- What do unarmed community service officers do when situations suddenly escalate?

- All public safety situations come with risk. Do you design law enforcement response for the average/typical scenario, or the atypical scenario, just in case?

- Are all observed discrepancies of outcomes mostly or fully explained by oppression or discrimination? Are we ignoring other factors that might also be at work?

- Are some of Seattle’s problem with repeat offenders not a police problem at all, but a problem of revolving justice?

- Is homelessness generally just a problem of affordability, not treatment (mental health or addiction) or other services? Do studies validate that?

- Do fewer police officers mean less crime and a safer community overall?

- Will a myriad of fragmented, private security forces (e.g., at larger retailers, perhaps for neighborhoods, gun-owning households, etc.) be a safer and easier-to-manage environment?

These and other questions will be put to the test in the coming years.

Real-world examples?

What cities serve as the best examples of what we’re trying to do? The example of Camden, NJ is often mentioned. But that story is also understood as one in which Governor Christie joined forces with police reform activists to essentially “union-bust” the police union. While it very temporarily did “abolish” the police, Camden now has more police officers on duty than it did before they were “abolished.” And Camden remains a high-crime city — in fact, it’s in the Top 4% of highest crime per capita in the nation; 96% of American cities are safer. Is that change we can believe in?

In the past two weeks, Seattle City Council has passed one of the largest progressive tax increases in the city’s history, and also signaled its desire to defund the police by half. None of this is directionally surprising to anyone following last year’s City Council election. Elections have consequences; I get it. They certainly appear to have full legal authority to enact these changes, and I’m not challenging their ability to press the accelerator on this bold new progressive direction.

But if we look at the recent experiment of CHAZ/CHOP, we see both that the SPD is in need of real reform in its unwarranted arrest and abuse of reporters and unnecessary use of force in teargassing protestors, but, with five shootings in a three week period, I’m also unconvinced we’ve seen proof that SPD standing down improves public safety. I’m not confining my views to this or that identity group. I’m talking about outcomes for all of us who call Seattle home.

Sworn Officer Levels

Comparison to Other Cities

One metric that’s used to compare police coverage is officers per 10,000 citizens.

Seattle’s population is about 730,000. So we have about 1190 officers covering 730,000 people, or 16 officers per 10k citizens. By comparison, that number for DC is 65, Baltimore: 46, Boston: 33, SF: 28, Atlanta: 30, and LA: 26 (source: governing.com.)

More To Come

I’ll be updating this running post over time with major developments related to public safety in Seattle.

Seattle ended 2020 with the highest recorded number of homicides in the past twenty years. And police officers are meeting Priority 1 Calls (emergency calls, the highest level) in the goal time in fewer than half of all calls.

I love this city, and I hope this turns around. We need to find a way to get beyond the division, the grandstanding, the posturing — and literally improve public safety. Since resource allocation is about tradeoffs, I think that begins with defining what the most important metrics are which indicate public safety, be clear about them, and then optimize those. Personally, I put things like response times, shootings, reports of assault and sexual violence and validated reports of law enforcement bias-crimes/brutality fairly high on the list.

Without getting clear about the metrics which matter most, we pretend that we can make major cuts in one area and “reimagine public safety” without having any clear idea of what may lie ahead, nor even being able to measure whether our decisions were the right ones.

Updates

March 9, 2021 — Brandi Kruse shares several slides from SPD showing how understaffing is leading to poor response times: