My wife and I are parents of two sons and a daughter, who are now in their teens and twenties. As we come out of COVID isolation and reconnect face-to-face with other parents, I can’t help but notice a theme. A surprisingly high number of parents of boys describe young men who are — for lack of a better term — struggling to chart their next step. Yet at the same time, most parents of daughters do not generally echo this concern.

There’s something going on with young American males in their “life’s launchpad” years, and few Americans wish to speak about it.

These young men attended the same schools as their sisters. They have loving, intelligent, driven and attentive parents. We’ve known many of these kids from a young age. And now, twenty years on, so many of the boys are opting out. They’re searching. Some are still in extended gap year. Three have dropped out of college. Those who aren’t in college don’t yet have full time jobs. They’re not apprenticing. In many cases these boys are living at home, or in apartments funded by mom and dad. In short — as they now hit their twenties, what Dr. Meg Jay calls the “Defining Decade,” they haven’t found their trail.

The daughters, by and large, are on a more determined path. They’re engaged at college. They’ve landed summer jobs. They have outlets and direction.

This is a very small sample size, and it could just be a unique snapshot. So try this. Know a parent whose kids were born around 2000-2005, who are now high school grads? Ask those with adolescent boys to give an honest assessment of how their son’s friends and peers are doing. Have they found purpose? Are they on the taxiway ready for liftoff? Then, ask parents of adolescent daughters how their friends are doing. Statistically, you’re likely to hear a very different picture.

Zooming out, the data from Pew, the Census Bureau the CDC and more tell a pretty consistent story. America’s young men are in a crisis which is worsening.

Boys’ high school graduation rates are 6% lower than females, and in some states 15% lower. Boys are twice as likely to have a substance use disorder. Boys are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, according to the CDC, which likely says something both about boys, and our tendency to intervene, medicalize and label otherwise normal-spectrum behavior a “disorder.” Boys are five times as likely as girls to spend time in juvenile detention. While females are more likely to exhibit suicide ideation, American males are 3.5 times more likely than American females to actually commit suicide.

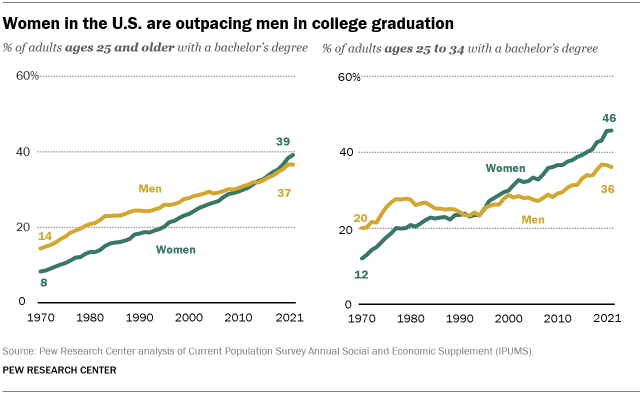

Across the country, college women now constitute 60% of the student body, and are also now clearly outpacing men in graduation:

Pew’s survey reveals that a significant driver is personal choice: “Roughly a third (34%) of men without a bachelor’s degree say a major reason they didn’t complete college is that they just didn’t want to. Only one-in-four women say the same.” Younger respondents are also far less likely (33%) than older Americans (45%) to say that college experience was “extremely useful” in helping them develop skills and knowledge which could be used in the workplace.

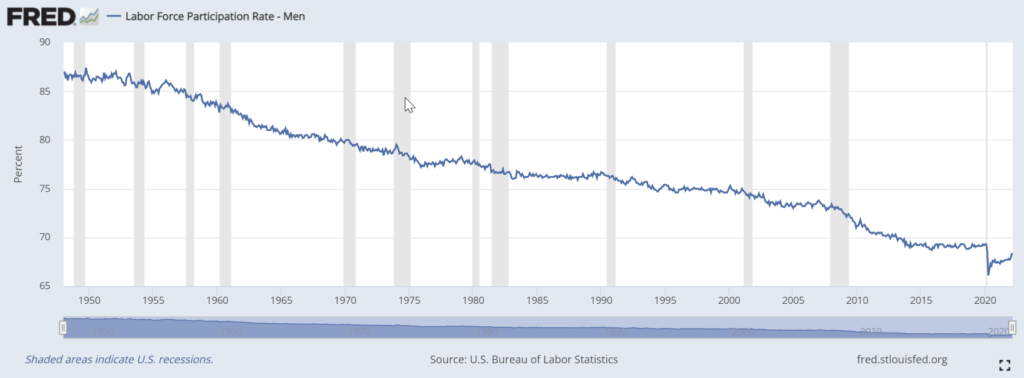

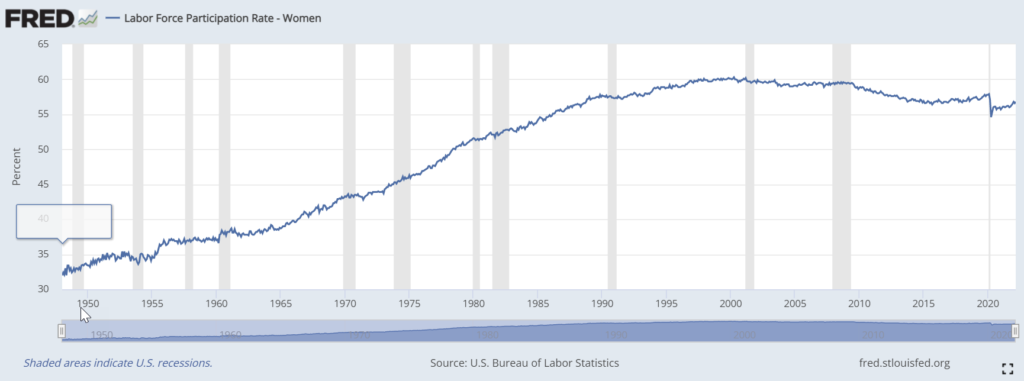

Male labor force participation rates have been on a steady decline since the 1980’s, while women’s has been on the rise. In 1960, 93% of men aged 25-34 were in the labor force; by 2021, that figure had fallen to 68%.

Not only are the snapshot statistics worrisome, but nearly every single one is trending in the wrong direction. The consequences for America are grave. NYU Professor Scott Golloway puts it starkly: America is producing too many of “the most dangerous person in the world: a broken and alone man.”

This isn’t just bad for men. 78% of American females report that a steady job is very important to them in selecting a spouse or partner. And fully half report that their mate must have equal or better education than them.

And yet, to sound the alarm — or worse, attempt to diagnose or work through whether any of this has cultural, sociological or pedagogical roots — brings out the pitchforks and vitriol.

Andrew Yang wrote a piece about this in the Washington Post in February, The Boys Are Not Alright. The most upvoted comment, from user IrisClover, is typical of the rejoinder: “I love the chorus of dudes proclaiming that male failure to thrive (i.e., to be superior) is all about an unfair system or current social conditions. Rampant violence against women, poverty, unfair pay, females doing nearly all unpaid labor, unequal representation for centuries…oops, they didn’t notice that.” Whew. Well, that conversation went well, didn’t it?

Far too many have conflated discussing the clear crisis in young men with rejection or pushback against the many wonderful advances for women, or a denial of celebration for all that’s been achieved.

But it should be possible to discuss the worrying trends without setting off bad-faith conversation about “what this really means.” Perhaps it means that the boys are in crisis, and we need to diagnose why. Perhaps it means that after three decades of focusing on female empowerment, we also need to ask, do men still have enough heroes, role models, and realistic goals they’re motivated to achieve? Perhaps an “oh, they’ll be fine” response isn’t quite hitting the mark.

We need to bring this conversation to the fore, and engage in it maturely, eggshells and all. It affects every single one of us. Somehow, through a combination of culture, parenting, schooling and more, we are exacerbating very bad trendlines for the future. Perhaps we should actually discuss it cogently, with data, and brainstorm some ways out of it.

After two decades of cultural emphasis on female empowerment, we need to add back to the conversation why and how tens of millions of young American males are opting out, standing on the sidelines, or otherwise falling through the cracks.